At 90 years old, Kenneth Anger is in fine, satanic spirits, still making art, films, and couture, and just having come off a hosting gig at a Halloween event co-hosted by DTLA gallery Lethal Objects. The event, which took place at Rudolph Valentino’s old mansion in Hollywood, was a celebration of the 20-year death-iversary of famous occultist and Satanic Church founder Anton LeVay. Equal parts memorabilia exhibition, spirited discussion, and black mass performance, the gathering brought together longtime devotees of both Anger and LeVay, two men whose work, by the late 1960s and far into the Satanic Panic period of the 1980s, would become fascinatingly intertwined.

But how did it all start?

When out-gay filmmaker Kenneth Anger met Anton LeVay in the mid-sixties, he was kicking around with a wild L.A. crowd whose fixtures included future Manson family member Bobby Beausoleil and singer Marianne Faithfull. LeVay, who christened himself the “Black Pope” of the Satanic Church, was actually one of the more vanilla members of Anger’s entourage, considering what went down on Cielo Drive in the later months of the Summer of Love. Between founding the Church of Satan and publishing “The Satanic Bible” in 1969, LaVey had taken a tip from his occultist forerunner Aleister Crowley and made himself infamous by the time the hippie movement was in full swing. His and Anger’s association – if no more than politely social – with Manson and his family was enough to cement LeVay in the minds of Americans as a dyed-in-the-wool demon, with just a touch of kitsch attached.

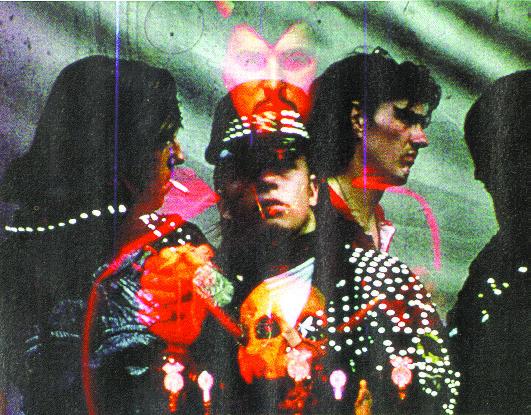

When Anger and LeVay began collaborating on what would become two versions of the same film in 1969, “Invocations of My Demon Brother” and its final cut, “Lucifer Rising,” a new visual language involving leather, sadism, gay culture, Hollywood camp, and the occult, became seamlessly combined in Anger’s seminal works. Many of the films Anger made in the 60s and 70s were deemed too obscene to screen by current standards. Anger’s 1963 film “Scorpio Rising” was at first banned in California by an all-female jury who found themselves shocked by its graphic nature. This, one guesses, was Anger’s intent, as he described “Scorpio Rising,” according to unauthorized biographer Bill Landis, as “a death mirror held up to American culture… Thanatos in chrome, black leather, and bursting jeans.”

America would tire of gazing into this “death mirror” by the late ‘60s, after the Manson murders rocked the country, and Hollywood starlet Jayne Mansfield who, along with Sammy Davis, Jr., had fallen under Anton LeVay’s spell in 1967, lost her life in a tragic, brutal car accident the same year. Some wanted to blame LeVay for a “curse” he put on Mansfield and her lover, who had been driving the car. A new documentary, “Mansfield 66/67,” coyly suggests as much while trying to shed a light on LeVay’s magnetic power over his followers.

When LaVey passed away in 1997 of heart failure, Satanic panic was on its way out, and Kenneth Anger still had a hefty career ahead of him. His juicy tell-all “Hollywood Babylon” had been re-released in 1975 (after being banned on its first publication in ‘65,) earning him a secure place in Hollywood history, and would go on to spawn not one but two sequels. “Hollywood Babylon II” was released in 1986, and “Hollywood Babylon III” is on the cusp of release. The first edition of the original “Hollywood Babylon” bears a picture of LeVay devotee Jayne Mansfield posed scandalously on the cover.

Today, LeVay and Anger’s version of Satanism seems so vague and artistically interpreted as to appear almost quaint. It’s the perfect campy non-religion for today’s Hollywood, a place that has long since left behind its scandalous, murderous reputation and replaced it with a host of yoga and meditation studios which, with their promise of spiritual restoration, bear a strong resemblance to the vagaries of LeVayan occultism.

Lethal Amounts Gallery owner David Fuentes, a longtime LeVay enthusiast, sees the Church of Satan as having been oddly progressive for its time, hence the newed interest of Angelenos in LeVay’s life and work.

“Openly inviting to gays, lesbians, non-conformists, and radical thinkers. The religion was for the intellectual elite, empowering the concept of self-acceptance and ridding the guilt of carnal delights.” Wrote Fuentes. “The message was if you couldn’t enjoy the thrills of life, what is the point of life itself?”