In the 1960s in L.A., queer life was all about small acts of rebellion.

You might know Long Beach as a new queer enclave, populated by thriving gay bars like the Mine Shaft and The Brit. And while yes, Long Beach is certainly on the come-up in terms of L.A. and L.A.-adjacent gayborhoods, it’s had a longer history of resistance than most. For instance: Did you know that Long Beach was the site of an early ruling that made oral sex illegal?

Most Colonial-era states in the U.S. had followed the United Kingdom’s lead by making sodomy a punishable offence. In 1776, Thomas Jefferson created a law that would cause men participating in gay sex to be castrated. Shamefully enough (but not too surprisingly,) these early laws stayed in place in many states until the 20th century. The famous case of Lawrence v. Texas was the last anti-sodomy law to go, having passed in 2003.

But let’s turn back the clock a bit: In 1914, sodomy may have been illegal in America, but oral sex definitely wasn’t. We can easily speculate as to why this was: Oral sex, much like lesbianism, was alternately thought not to exist and found too hard to describe for the purposes of creating and enforcing hateful legislature. This all changed when the Long Beach Police Department decided to raid two gay clubs in 1914. According to Lillian Faderman and Stuart Timmons’ book “Gay L.A.,” these raids changed everything:

“[Police raided] the 606 Club and the 96 Club, and arrested 31 men, who were accused of fellatio. Sodomy had been a felony in California law since the 19th century, but oral sex had not been. The whole incident was interesting because it was one of the first incidents of police entrapment. The arrests received major attention. Several newpapers published a ‘List of the Guilty Ones’ and one man, John Lamb, committed suicide. As a result of those arrests, Long Beach passed a law making oral sex illegal. The following year, the California legislature passed a bill outlawing oral sex. The law remained on the books in California until 1975.”

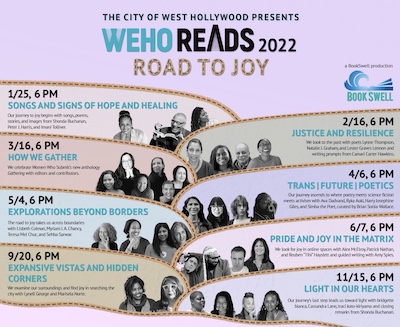

Damron’s Address Book showed LGBTQ+ visitors where to go for friendly fun–and where to stay away from.

Later on, another Long Beach incident made waves, a year before Stonewall and some months after the Black Cat Protests. Long Beach citizen Lee Glaze staged a riot at the bar he owned, The Patch, in 1968, when police told him that his bar had to ban drag and male-on-male activity in order to stick around. Glaze didn’t take this lying down. He allowed men to keep dancing with each other, prompting a raid that turned into a full-on ‘60s-style sit in when:

“Glaze and the patrons went to a nearby flower shop owned by one of [The Patch’s] patrons and bought all the gladioli, mums, carnations, roses and daisies. At 3 a.m., the demonstrators carried huge bouquets into the Los Angeles Police Department Harbor Station and staged a “flower power” protest as they waited for the arrested men to be released.

Meanwhile, another gay man was paving the way for queer community. Bob Damron, a bartender working in L.A. in the 1950s, ran a bar named the Red Raven on Melrose Place. In his spare time, he teamed up with Mattachine Society President Hal Call to publish a few copies of “The Address Book,” a handy manual letting LGBTQ+ tourists and citizens know which places around town were safe to hang out in, which places were fun for a certain type of sex, and which were hostile. The first edition of the book was printed in 1965, and it told a million stories with each abbreviation (C for coffee house, RT for raunchy types, etc.) Before Stonewall shook the world into action, smaller, defiant actions like Glaze’s and Damron’s helped a culture of queer folks unite inside of a city that would become one of the most exciting LGBTQ+ capitals of the world.