Across the country, from Stonewall to the Black Cat to Compton’s Cafeteria, the queer youth of the 1950s, 60s and 70s worked hard to fight against oppression and intolerance. Today, one full year into the Trump Administration, we’re looking back at how the protests and cultural movements of the past have shaped L.A.’s current queer culture.

Lesson One: Persist

They raid one place, we find another. In the early days of gay bars in L.A., raids were a not-infrequent problem for patrons who just wanted to grab a drink and flirt at will. Lesbian bars like ‘50s favorite The Party Pad on Vermont Ave. became targets for L.A.’s Vice Squad. One cop, after seeing the girl-on-girl vibe inside the bar, labeled it ‘injurious to public morals’ and arranged a raid. Other lesbian bars like Anna’s in Silverlake, where, according to a patron, “all of us young people, nobody over 23 or 24, [danced] together,” met the same fate. The Vice Squad kept coming after gay bars on the flimsiest pretenses, often claiming that lesbian patrons were prostitutes in order to book them en masse. In gay male bars, the Vice Squad felt free to get physically violent. However, L.A.’s queer culture persisted. We may have lost a ton of great gay bars along the way (RIP, “The Waldorf”) but more importantly, we’ve put down roots here and re-designed the city in our own image, from Silver Lake to West Hollywood and beyond.

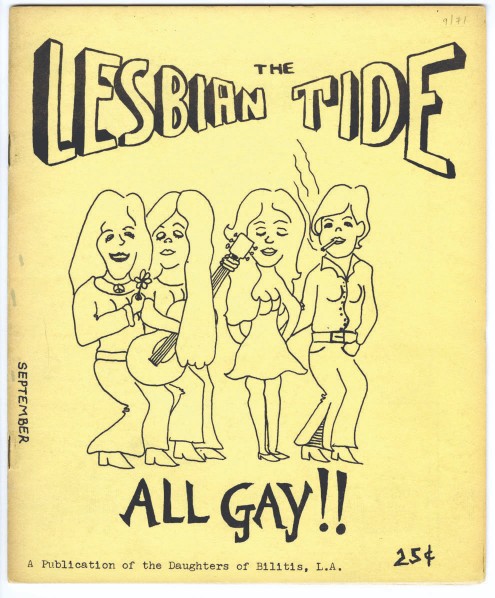

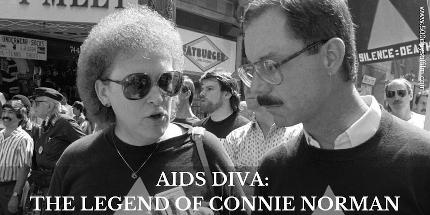

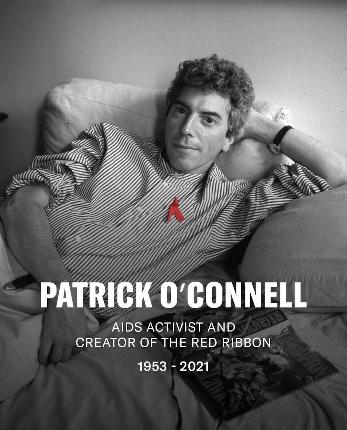

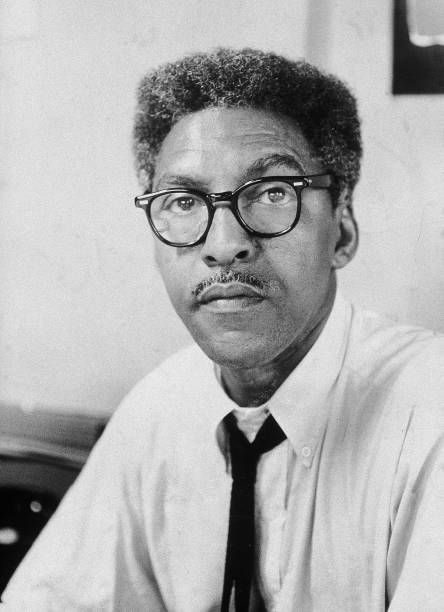

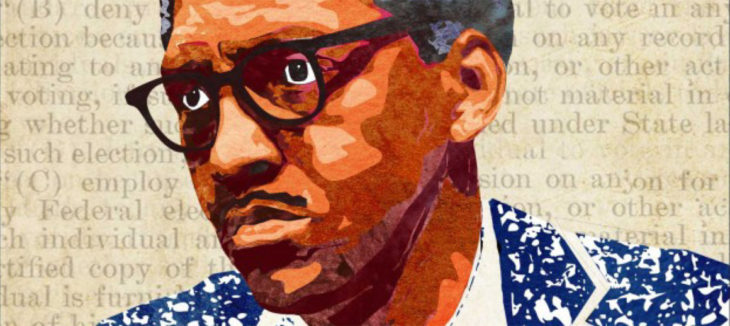

Lesson Two: Organize

Bodies on the street. Thanks to the early efforts of Christopher Street West in the 1970s, L.A. developed a proud protest culture. From the Cooper’s Donuts riot in 1959, where a young John Rechy witnessed trans, gay, and lesbian patrons being harassed for no reason, to the Black Cat protests against police brutality in 1967, we’ve had plenty of examples of how to fight the powers that be and protect our individual liberties. In 1942, with WWII underway and women taking over the workforce in large numbers, L.A.’s then-mayor Fletcher Bowron tried to create a regulation to prevent female City Hall workers from wearing pants due to his distaste for “masculine women.” During this time, women could even be arrested for looking too masculine, under the charge of “impersonating” a man. Much later on, when the AIDS crisis broke out, L.A.’s LGBTQ+ population took to the streets to let the laissez-faire government know that silence and passivity were not options.

Lesson Three: Become Ubiquitous

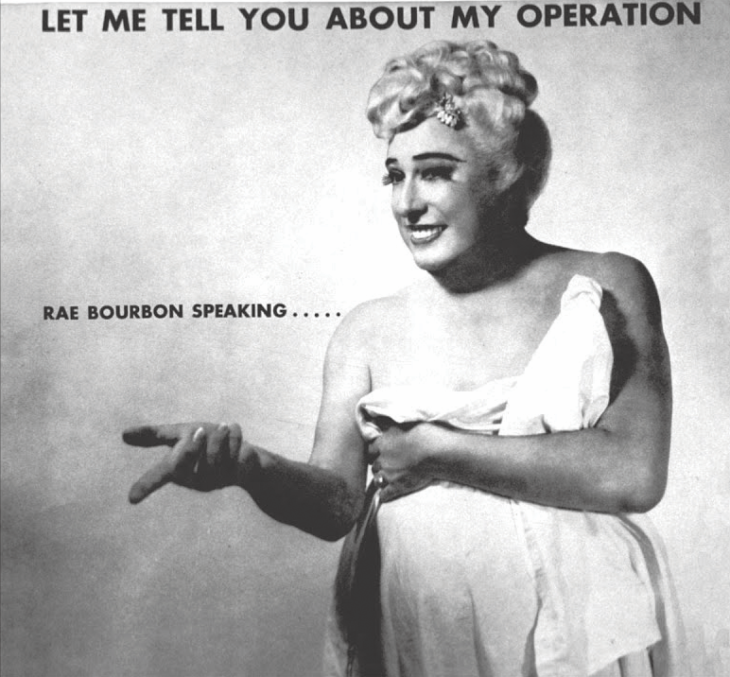

We are legion. From the earliest days of Hollywood, when the film industry was just a group of people with clunky box cameras and a couple of horses, queer actors, directors, producers, and DPs have been churning out cinematic masterpieces. From the 1910s to the 1920s, Hollywood was full of gay leading men who created a new, edgier brand of romantic masculinity in the movies. Starting with J. Warren Kerrigan, who lived with his mother (and his boyfriend) leading up to William Haines, queer men were huge box office draws who allowed female (and male) viewers to indulge in a fantasy of liberated sexual desire. Early Hollywood was also full of queer directors, like William Desmond Taylor and Dorothy Arzner, who made films that actively fought against the male gaze to portray powerful actors like Katherine Hepburn (in Arzner’s 1933 film “Christopher Strong”) in a feminist light. Later on, directors like George Cukor and screenwriters like Gore Vidal would continue to create complex, fascinating queer stories onscreen and selling them to the public at large.

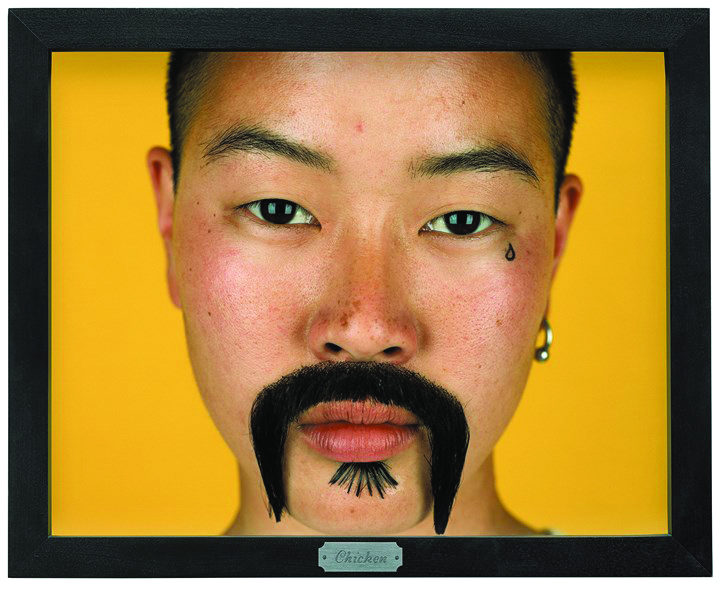

Lesson Four: Don’t Forget to Have Fun

Dance, dance, dance, honey. From raids to revolts to straight-out violent arrests, L.A.’s LGBTQ+ elders waded through a ton of trauma to help us get to where we are today. But they didn’t do it without taking a bit of time off to enjoy the culture they were creating. Descriptions of 50s-70s era gay bars in L.A. are snippets of paradise lost, when queers from all over would convene to dine, dance, and enjoy the safety and love of each others’ company.