Last year at this time, a weary nation was gearing up to launch a series of significant, country-wide protests on Inauguration day. The resulting marches in Washington, New York, and Downtown Los Angeles made the country sit up and take notice, setting the tone of a politically-charged year of feminist victories and queer triumphs.

As significant as last year’s marches were, they didn’t come out of nowhere. Los Angeles has a long history of early-in-the-year political protests organized by minority citizens who, newly energized by the New Year, get together to stick it to the current regime.

We’ve spoken about L.A.’s history of queer resistance, from the famous pre-Stonewall Black Cat protests to the Christopher Street West Parade (later to become the L.A. Pride Parade) to the “Gay-Ins” at Griffith Park in the 1960s and 1970s. But it was 47 years ago, in 1971, that L.A.’s queer and Chicanx communities came together to hold the LAPD accountable for what had been the very violent year of 1970.

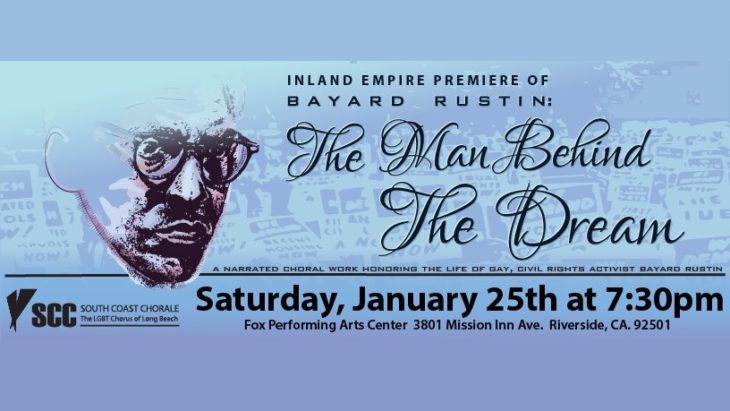

The Silver Lake Black Cat Protest in 1967 marked L.A.’s first queer anti-police brutality protest.

On August 29, 1970, three Los Angeles citizens lost their lives during the Chicano Moratorium march and Vietnam War protest in East L.A. After the death of L.A. Times journalist Ruben Salazar via tear gas pellet, the community turned to the L.A. Sheriff’s Department for answers. Though the Sheriff’s Department maintained that Salazar’s death, along with other protestors at the August 29 march, was accidental, the community was not satisfied. Salazar’s death prompted the famous Hunter S. Thompson to write “Strange Rumblings in Aztlan” for Rolling Stone, a piece that chronicled how the sudden, violent killing of Salazar changed a peaceful protest into a chaotic scene and mobilized the Chicanx community into action.

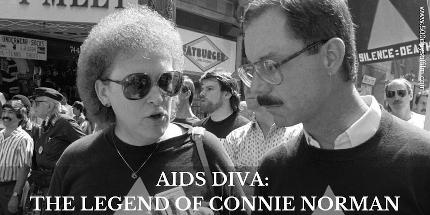

Protesters in February of 1971 held posters calling out police brutality against LGBTQ+ citizens.

It was because of the shocking events of August 29 that the January 31, 1971 protest against police brutality took place. On that day, over 7,000 citizens marched on East L.A. to be greeted by armed policemen ready to open fire. At the end of the march, they did, wounding many and arresting over 100 citizens.

The January 31 protest and its violent aftermath were acknowledged by many as marking the end of the Chicano Movement on the 1960s and ‘70s. However, the legacy of the Brown Berets paved the way for a year of community protests against police brutality and government corruption. After the 31st, LGBTQ+ Angeleans took to Hollywood Boulevard to protest police brutality and the high number of arrests (and violent treatment) of gay men in the years previous. Later that year, weeks of anti-war protests would lead to a gigantic march on Washington led by the Mayday Tribe, a group of 25,000 students and activists whose slogan read: “If the government won’t stop the war, we’ll stop the government.”

A year beforehand, in 1970, the first L.A. Gay Pride Parade had made a splash on the streets of Hollywood. It had also led to 14 arrests for same-sex kissing (then illegal in public) and beatings of protesters by the police in attendance. By 1971, L.A.’s queer community knew how to organize in a way that couldn’t be ignored. When they took on police violence that February, they were helping to cement a new standard of non-violent protesting, started in part by the Chicano movement, that would take the community into a new era of civil rights battles.