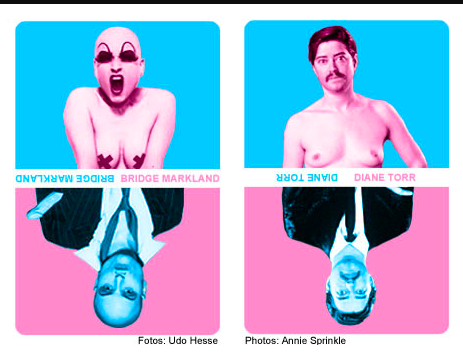

When artist Diane Torr donned her first mustache in public, at an art opening at the Whitney in 1989, she didn’t know what to expect. Some people put on drag as a disguise, to better blend in with the outside world. Others do it as a performance. Torr used drag as an experiment: A way to see another side of life. And see it she did: It took people no time at all to start treating her differently as a man. Friends she’d had didn’t recognize her. Women tried to hit on her. Men paid her respect.

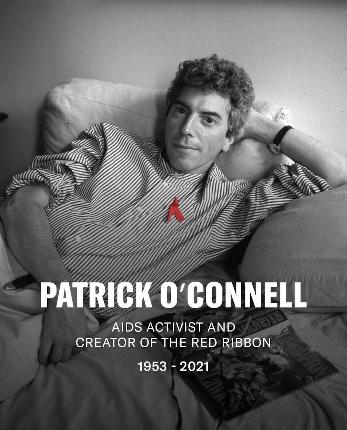

For Torr, who died last month at the age of 68, this work was the beginning of a lifelong experiment. She wanted to pin down the ways in which life was lived differently across gender barriers, and her research was never finished.

Canadian-born, Scotland-bred Torr always had a hard time fitting neatly into the labels the art world gives out. Was her work performance art? Pure drag? Multimedia? Was it dance? And what about her ‘90s workshops, “Man for a Day,” in which she would teach the art of drag to aspiring drag kings? Was that art, too?

Torr paved the way for a kind of thinking about gender that was not yet fully in vogue yet. As a contemporary of Judith Butler and Jack Halberstam, Torr was slightly ahead of the curve in her performative, critical work on gender, in which she took Butler’s nascent academic theories to the street to play them out in real life. She developed characters, mixed secondary sex characteristics in public, and eventually compiled her lifelong research in two books, “Sex, Drag, and Male Roles: Investigating Gender as Performance” (2010) and “Man for a Day” (2012.) In later life, Torr enjoyed a visiting professorship at Glasgow School of Art.

As a curious, intrepid gender activist, Torr was never done exploring the topic of gender crossover. Until the end, she was doing shows and workshops and compiling her observations in writing. And until the end, she never stopped asking questions. In a TEDx talk given in Hamburg in 2016, Torr spoke about her early life. “In those early days performing in New York in the ‘70s and ‘80s, I was not aware of the revolutionary possibilities of the work [of drag.] Of its ability to create something new.” For a whole new generation of artists, scholars, and curious thinkers, she made us aware.