When the police came for marginalized groups in the 1950s, a near-alliance was formed between two of L.A.’s most beleaguered (and intersecting) groups.

The 1950s in Los Angeles proved a violent decade for many underserved communities who didn’t fit into the cookie-cutter vision held by many lawmakers and politicians for a post-war America. As a result, the decade before the start of the civil rights movement saw countless raids, racial profiling incidents, and downright violence aimed at queer and other marginalized communities.

After the formation of the Mattachine Society in 1950, founder Harry Hay and his fellow leaders were trying to protect their fellow members from targeted raids on gay bars and community spaces. By 1952, after the arrest of another Mattachine founder, Dale Jennings, was arrested for soliciting sex in MacArthur Park, Hay was trying to find a way to bring peaceful, yet provocative action against the police force. During this time, he was contacted by another organization interested in keeping the peace. The Civil Rights Congress, a communist organization closely tied to L.A.’s large Mexican-American community, made contact with Hay to see if the Mattachine society might combine forces to present a united front against police brutality.

The LAPD had been targeting Latinx community centers in the same way they’d been raiding gay bars in the city. When it came to L.A.’s Mexican-American community, police brutality largely got swept under the rug even if an incident, such as the 1951 arrest of six young Latino men, turned violent without reason, an incident that novelist James Ellroy would later draw inspiration from when writing “L.A. Confidential.” Harry Hay and the other Mattachine Society members were watching closely and thinking about creating a protective alliance with the other targeted individuals who’d had enough of bowing to the LAPD’s violent whims.

“As soon as we got into the oppressed cultural minority phase we had something our backgrounds had prepared us for—oppression of the blacks, the Jews, of women, and now—here in Los Angeles—of the Chicanos…” said Mattachine cofounder Chuck Roland. “A left-oriented organization, ANMA (Asociación Nacional Mexicana [sic] Americana), was formed to oppose police harassment and frequent brutality in East LA. We would make common cause with them for, we were convinced, all socially oppressed minorities had something in common, whether they knew it or not.”

ANMA would be a force for justice in the coming years, with branches all across the country. The organization was interested in calling the police force to task for using covert operations and plainclothes insurgents to entrap and imprison Latinx community members. In 1952, five Mexican-American youths found themselves nearly murdered due to an entrapment scheme that affected both queer and Latinx communities: A vice squad officer, attempting to solicit one of the young men in the men’s room of the Echo Park Boathouse, ended by shooting him and arresting the others simply for trying to flee the scene.

After news of this incident spread, with the police and the press unable to suppress its clear homophobic undertones, Harry Hay reached out to Shifra Meyers, the current Administrative Secretary of the Civil Rights Congress, to express his outrage at the the treatment of both groups.

“What have you ever offered the Homosexual that he should risk his livlihood [sic], his housing, even his pitiful facsimile of social security, to inform you?” Hay asked. “Has any committee and/or group of civic or sectarian minded citizens ever taken even an impartial interest in the Homosexual Minority as a Group? Has the homosexual EVER had anyone to turn to, (except the dubious subjectivity of his own), for help, succour, guidance, protection, or sympathy? Unfortunately, well-meaning people like yourselves are still so shot through with Freudian conditioning that you cannot perceive the Homosexual as a member of a social minority.”

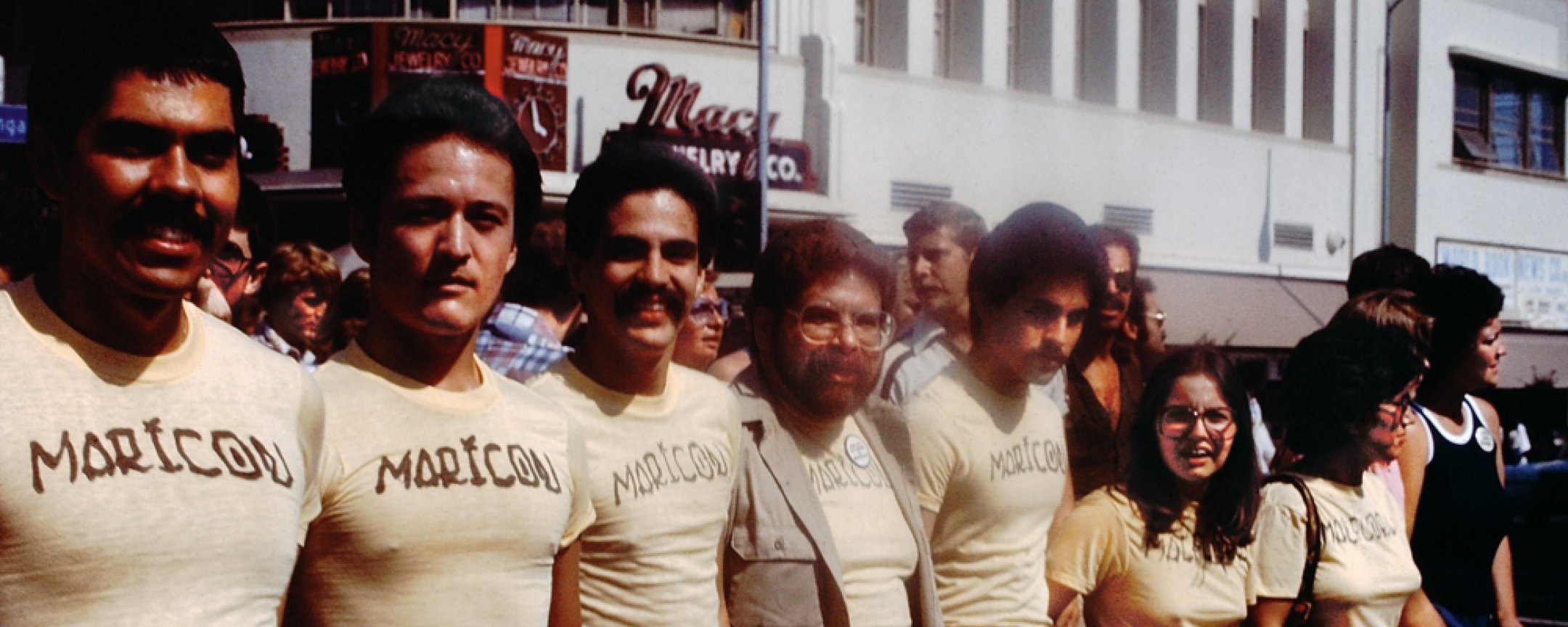

While the alliance didn’t amount to anything in the end, the conversations begun by Hay and the concerned members of ANMA paved the way for bigger, broader civil rights struggles to come. Perhaps Hay, without knowing it, was aware of just how much the queer and Latinx communities in Los Angeles have always bled into one another to create so much of the city’s iconic culture, imagery, and heart.