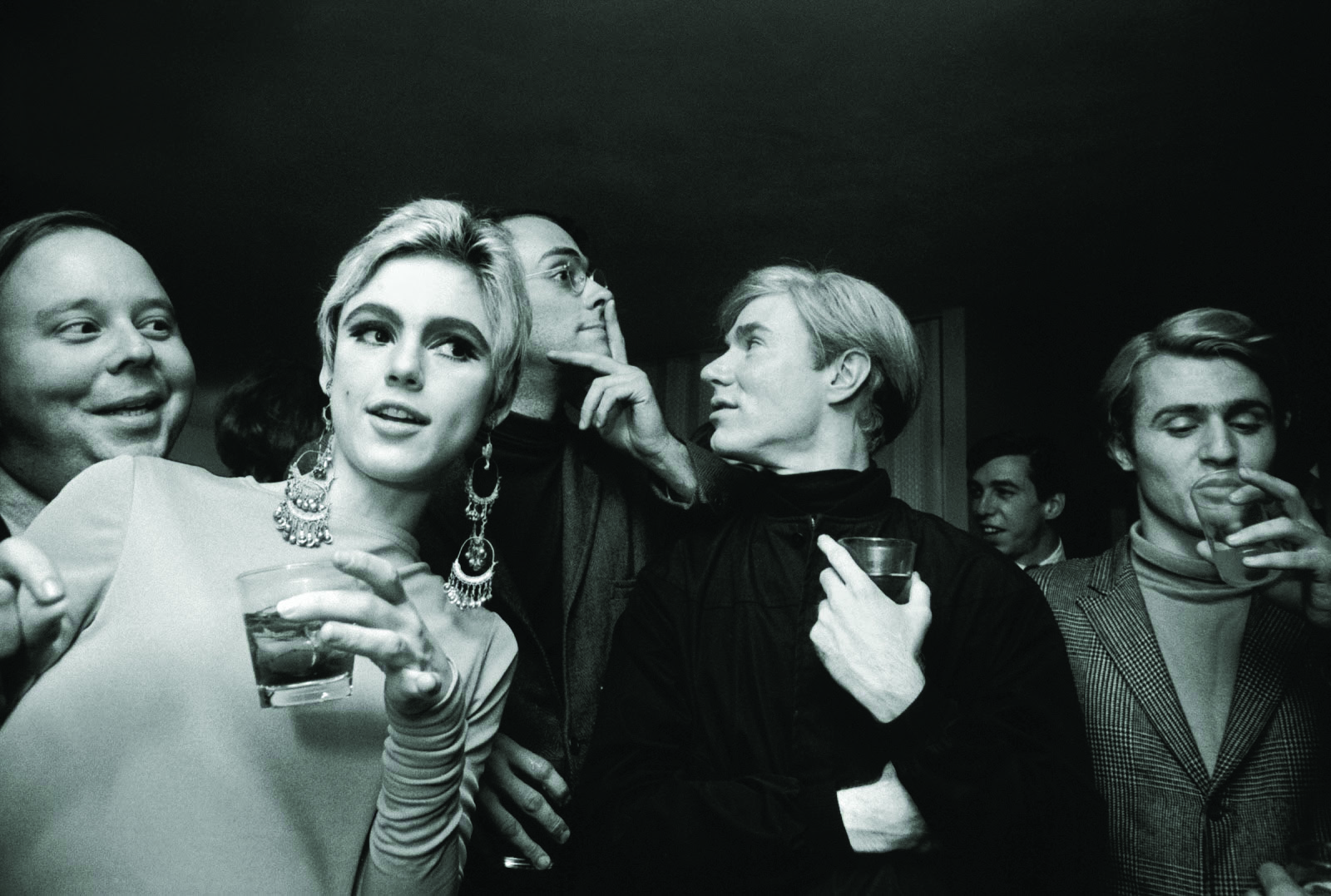

Research by J.J. ENGLENDER| Anthony Burgess’s 1962 novel “A Clockwork Orange,” which follows a violent misfit through a dystopian near-future, might have been an instant hit as a novel, but it still had a ways to go before making a big-screen impact. Even before Stanley Kubrick’s seminal 1971 film starring Malcolm McDowell as the vicious, volatile Alex, Andy Warhol had been struck by Burgess’s stirring tale of a society gone mad. So much so, in fact, that he decided to adapt it for the screen before Kubrick had secured the rights (or perhaps afterward – Warhol certainly hadn’t sought them out for his own work.) And by “adapt,” of course, we mean basically rewrite the entire book to include wild Factory parties, gimp masks, and Edie Sedgwick in her first speaking onscreen role.

A 1967 poster boasts a midnight showing of “Vinyl” in Los Angeles.

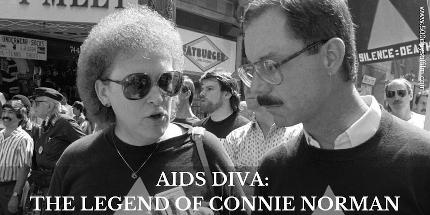

This was “Vinyl,” Warhol’s 16th film to date, screened at Santa Monica’s Western Theater in 1967 as part of its scandalous “Movies at Midnight” billing, featuring more titillating fare such as “Soul Freeze” (whose plot revolved around “mysterious sexual visions”) and “Mosholu Holiday.”

“Vinyl’s” scandalous life had begun in 1965, when it was released as a three-shot “anti-film” featuring scenes of gratuitous violence and a soundtrack by some of the most cutting-edge bands of the day, including The Kinks, The Rolling Stones, and The Isley Brothers. From the start, “Vinyl’s” appeal seemed tied to its relationship to music. In 1966, Warhol’s movie was screened at the Methodist Student Center in Austin, Texas. The event was billed as ‘an evening of expanded cinema’ and purported to feature a 5-D light show, featuring The Velvet Underground – who failed to show up.

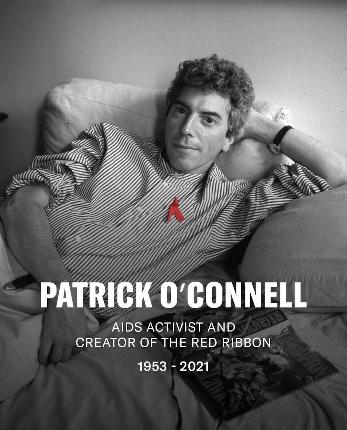

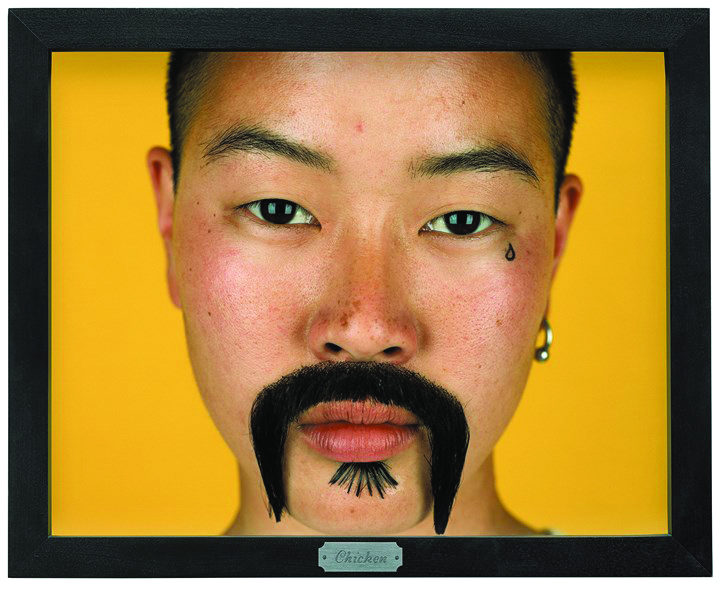

A preponderance of leather doesn’t phase the calmly smoking Edie Sedgwick in “Vinyl.”

Still, “Vinyl” drew in the crowds for a time on mere shock value alone. The typically slow, un-cinematic adaptation of Burgess’s classic novel is notable for its infusion of queer elements (ahem, leather) into a mainly heterosexual story. While Burgess’s novel – and its famous Kubrick adaptation – both focus on the uncomplicated sadism of the near-future, Warhol chooses (as usual) to focus on the other half of the sadomasochistic equation. Without being anything like a faithful adaptation of the book, Warhol’s version adds an important addendum to the original text: Sadism can only live and thrive in a masochistic world. “Vinyl” is almost an optimistic take on the traditional bleakness of “A Clockwork Orange,” and a more forgiving one than most.