L.A.’s first official Pride parade was held June 28, 1970, just one year after the start of the Stonewall riots in New York. The years before the first pride march had been defined by violence, police raids, and targeted protests by a queer community that was just starting to take up arms against oppression. In May of 1959, trans women in L.A.’s “Skid Row” neighborhood found themselves taking arms against a sea of cops by chucking doughnuts and coffee cups for their own protection at Cooper’s Donuts. In 1966, a raid on the Black Cat Tavern in Silver Lake spurred another round of protests from queer folks who had had their fill of police persecution.

In May of 1969, the L.A. City elections found queer people rioting against the appointment of openly-homophobic District 13 council member Paul Lamport (who claimed that gays were “molesters.”) In November of the same year, Reverend Troy Perry, enraged about his boyfriend’s recent arrest after a raid on the Patch Bar, organized a protest in Downtown L.A. calling for reform of the homophobic laws that existed to put gay men behind bars. In March of 1970, 200 L.A. citizens marched on Downtown’s Main Street in memory of the murder of Howard Effland, a gay man who had been beaten to death by police officers at the Dover Hotel.

By the time the one-year anniversary of Stonewall rolled around, L.A. queer activism had already been flexing its growing muscles in the face of injustice for some time. The seeds for Pride had been planted and sewn by widespread discrimination and violence. On June 28, the queer community came out in full force to make sure its numbers would be seen, heard, and recognized. The revolution had already begun. Now it had a name.

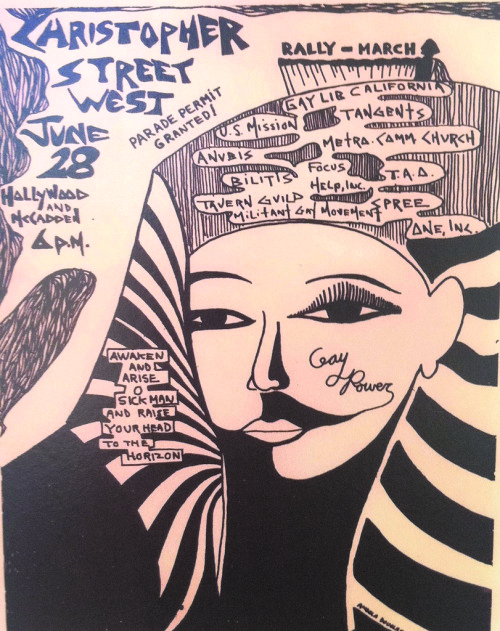

The Christopher Street West Parade, as it was initially named, had a rocky start. Organizers were denied a parade permit unless they could guarantee $1.5 million in securities, a ridiculously high number that no one expected the organizers to be able to pay. When Herb Selwyn, the attorney for the Mattachine Society, got involved in the process, he fought the police commission’s discrimination and won the parade its permit. An early poster for the event proudly advertised the fact, inviting queer folks and allies to come rally at the intersection of Hollywood and McCadden: “parade permit granted!” Bob Humphries, Morris Kight, and Reverend Troy Perry planned the commemoration parade, plotted out its course, and went about the near-impossible task of organizing a march to promote the rights and visibility of a group that was still, by and large, criminalized in the state of California. Within days of securing their permit, they’d planned the entire march with government-granted LAPD protection guaranteed for marchers and spectators.

It wasn’t just a monumental win for gay rights – it was one of the first moments in American history when a denial of fundamental rights for queer folks was seen as a direct contradiction to the American constitution.^o This year’s march, with its theme of political resistance, has been set up as a kind of supplanting of the usual celebration. Instead of marching for Pride, we march for change. But for the queer community in Los Angeles, Pride has never been just about celebration. It’s been about challenging the status quo, fighting for reform, and keeping sight of how much more work is still to be done. The #Resist march is perfectly in league with the spirit of L.A.’s first pride celebration. It’s a rallying cry: We must change our country, and that change has to start here, in our own backyard.