Try, if you can, to imagine LA as a different city: Fewer cars, winding roads, and the kind of city planning that even Waze might have a hard time simplifying. Oh, and no highways. Can you picture it? Neither can we. Thanks to 20th-century transportation icon Jacob Dekema, we don’t have to.

The former district director for Caltrans passed away at the age of 101 last month, leaving behind a legacy that shapes the way we think about travel in Los Angeles. Much in the way that Robert Moses controversially re-shaped Manhattan transportation by introducing bridges and highways leading into the city, Dekema created the backbone of what would become the national interstate highway system, not to mention the most iconic part of the California landscape.

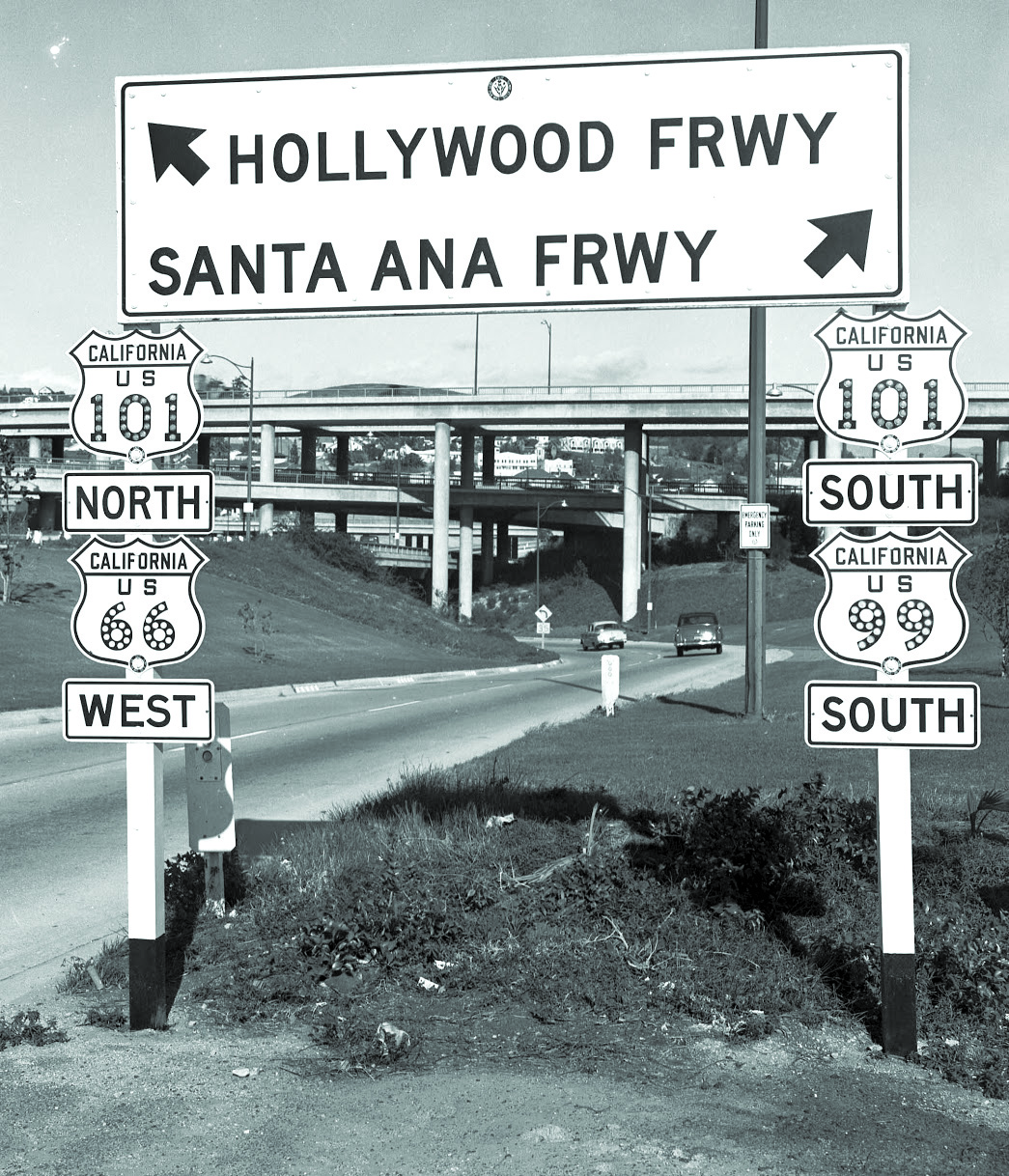

Known alternately as “Mr. Freeway” and “Mr. Caltrans”, Dekema graduated from USC in 1937 and went on to lead a brilliant, sometimes controversial career as head of San Diego Caltrans from 1955 to 1980. During his tenure, he made decisions that would radically shape the rest of the state, crucially the city of Los Angeles. His ‘50s sketches became the basis of the Interstate Highway System. His first task, back in 1936, was to help design the first freeway in the West–the then-named Arroyo State Parkway, now known as the Pasadena Freeway. At Dekema’s insistence, the highway, originally conceived as a four-lane structure, was expanded to six lanes, an addition no one else thought would be needed.

His time as district director was not without its struggles. Detractors felt that Dekema was building too many freeways, while Dekema lamented the impossibility of building more in his lifetime. His designs were focused on creating more abilities for through-traffic without constricting the potential for beautiful cityscapes. He was also mindful of running freeways through the heart of the many smaller communities that make up most California cities.

In the ‘20s, the first U.S. Numbered Highway system was adopted in California, replacing a number of confusing “national auto trails” leading from East LA to Santa Monica. It was the first attempt at the kind of grand organization Dekema hungered after–a way to ride through and supersede the more sprawling parts of the Los Angeles landscape without crushing its character. The Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956 was passed by Eisenhower in the same spirit. Eisenhower’s desire to connect the nation through highways was of a piece with Dekema’s vision for his home state. His idea of the future was of a vast, scenic web of land connected by smaller, snaking pathways and through-ways. Dekema designed his work to reflect, and take advantage of, California’s stunning beauty.

He was also thinking about how Californian city-dwellers live and work. In a San Diego Magazine interview from 1980, he predicted that: “the worse the traffic gets, the faster the electronic revolution develops. It may well be that mass commuting will no longer be needed. People will be able to stay home and work, or they’ll work in small offices, spread out all over the city and countryside, linked by computers and sophisticated communication systems.”

In 1982, the I-805 at Sorrento Valley was named affectionately after him. Dekema passed away in La Jolla of natural causes. He is survived by his daughter Pamela, his wife Shirley, and his son Douglas. Oh, and the massive, living achievement of the California highway system.

It’s nearly impossible to imagine was LA culture would be without its freeways. From the length and structure of the daily commute to the opening scene of ‘La La Land’, Angelenos owe more than they know to Jacob Dekema.