Richard Hall’s stories are unflinching about gay life. So why isn’t he remembered more widely?

It’s no secret that during the ‘80s and ‘90s, we lost some of our best writers, musicians, artists and thinkers to the AIDS crisis. Not only that: we lost some of our bakers, our servers, our bartenders, our public servants, our lovers, our friends. In short: we lost.

Writers like Edmund White, Armistead Maupin and Larry Kramer have documented this in their work. Even if they hadn’t become famous for writing about a time that most people who didn’t live through can’t fathom, they would have been able to have the last word simply due to their survival. It’s said that history is written by the victors. In the case of queer history, it’s written by the survivors, who are their own kind of victors.

Among the people randomly picked off by the AIDS crisis was Richard Hall, a writer who died in 1991, just two years after the death of his partner. Rather than ending with his death and letting it define him, et’s start with it and work backward. During his life, Hall distinguished himself by writing short stories, plays and murder mysteries with gay people – and gay life – at the center. From 1976 to 1982, Hall wrote a regular column for the Advocate (which, sadly, has not been digitized.) He was the first out-gay person to be elected to the National Book Critics Circle. Today, none of Hall’s books are in print.

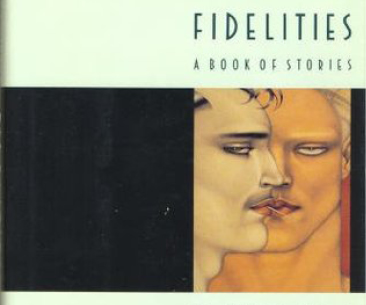

“Fidelities” and “Couplings” were among Hall’s short story collections.

I was lucky enough to find a copy of Hall’s “Letter From a Great-Uncle” in, of all places, the playwright Edward Albee’s library in Montauk, New York. The 1985 collection published, like most of his others, by San Francisco’s extinct Grey Fox press, is slim, with the title story making up the bulk of it. The format of “Letter From a Great-Uncle” uses an extremely traditional format to talk about an unconventional man. The story begins when the narrator – a stand-in for Hall himself, who likewise had a gay uncle – is on his way to his home in San Francisco when he is spurred by a memory of being 10 years old and being given a promise by his Great-Uncle Harris to tell him his life story. When Harris dies before he can keep the promise, the narrator is forced to delay his San Francisco trip with a detour to the family hometown of Gideon, Texas, to read a sealed letter written by his Great-Uncle explaining his life. Harris’s letter describes growing up in frontier-era Texas right after the Civil War, and slowly realizing his homosexuality. His father finds out and sends him to a mental institution-cum-primitive conversion camp, where other inmates’ testicles are routinely removed in order to ‘cure’ them of their sexuality. Uncle Harris escapes and makes his way to New York city where he lives out his life as a proud “Yankee.” and an out gay man.

The narrator realizes that, by breaking the seal, he has become the first and only person to learn the true story of his uncle. In the last line of the book, he admits that very likely, of the people who knew and survived his family, “not one of them, I’m quite sure, remembered Uncle Harris.”

Today, Hall is one of the many people whom history has, likewise, chosen not to remember. Looking online, one can only find a handful of resources about him, mostly linked to out-of-print books and essays about his work. One such book, “The Lost Library: Gay Fiction Rediscovered,” carries a touching tribute to to him by the writer Jonathan Harper. In the essay, Harper tries to use Hall’s work as a way to relate to one of his lover’s standoffish friends. “The source of my empathy,” Harper writes, “was a fiction book by a deceased, out-of-print author that he’s not even going to read.” Still, he makes an attempt, using Hall to tie two people in the same community together.

Remembering people and their lives isn’t just about saying their names aloud or running them off in a list. It’s about trying to hold space in your memory not just for who they were, but for what they were trying to do and say. Not all hope is lost for Hall of course: A project is afoot to turn Hall’s “The Country People” into a film. Perhaps a new generation will come across a copy of “Fidelities” or “Couplings” and find something to love inside of it. Let’s hope so: After all, there’s a lot to love there.