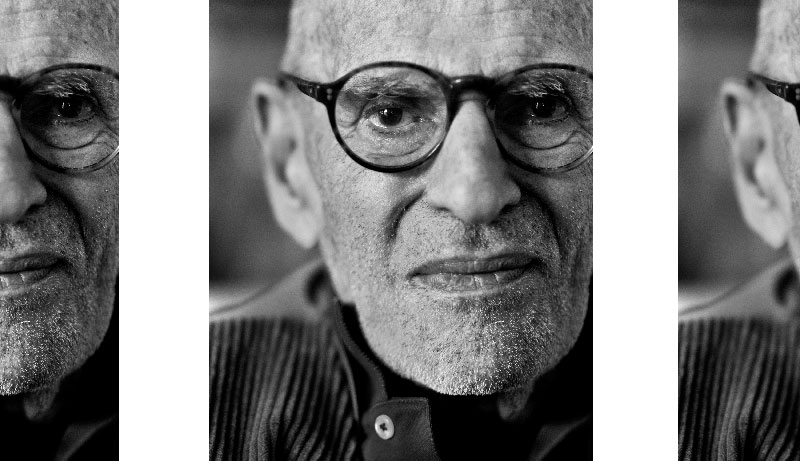

BY MAER ROSHAN | Few people in the past five decades have played as pivotal and public a role in the gay rights movement as Larry Kramer, the combustible author, playwright and AIDS activist whose leadership radically transformed gay culture and politics almost overnight.

Soft spoken and unfailingly polite in person, Kramer has always been something of a public lightning-rod.

Born to a Jewish family in Connecticut and educated at Yale, he began his career rewriting scripts for Columbia Pictures and penning screenplays of his own on the side. In 1969, while working in London, he wrote the screenplay for Women in Love, a screen adaptation of DH Lawrence’s classic novel. The film secured Kramer an Academy Award nomination and established him as one of the most prominent openly gay industry people in Hollywood.

A prolific playwright and essayist, he has frequently used his writing as a vehicle to air his oft-controversial views about a community that both delights and disappoints him. In the ‘70s, well before the advent of AIDS, he raised hackles with his novel, Faggots, a searing indictment of what he viewed as the shallow, promiscuous sexual culture that pervaded gay male culture. (Angry critics of the book denounced its author as puritanical and prim.)

When the first cases of “Gay Cancer” began surfacing in the early ‘80s, Kramer was among the first to raise the alarm. He used his column in New York’s gay newspaper, The Native to attack the deadly indifference of the medical and political establishment, and warned gay men that the only way they’d survive the plague was if they stopped having indiscriminate sex and stood up for themselves.

Kramer’s efforts resulted in the formation of Gay Men’s Health Crisis (GMHC), which went on to became the largest private AIDS service organization in the world. But as the epidemic continued to claim an army of his friends, Kramer became increasingly angry and more radical. Combative and sometimes self-righteous, he grew frustrated with the bureaucratic paralysis and the apathy of gay men to the AIDS crisis, and denounced gay men who chose to stay closeted rather than publicly fight the epidemic.

Among Kramer’s most frequent targets was the city’s then-mayor, Ed Koch, who happened to live in Kramer’s Fifth Avenue building. Whenever the two men occasionally crossed paths at the elevator, Kramer would determinedly avoid the mayor’s gaze and address his dog. “Look Molly, “ he’d growl, “there’s the man who’s killing all daddy’s friends.”

In 1985, Kramer channeled his mounting frustrations into an autobiographical new play, The Normal Heart, produced by New York’s Public Theater. Released to rapturous reviews, the play served as an early history of the AIDS crisis and an angry indictment of organizations like GMHC, whom Kramer saw as passive and politically impotent.

Two years later, while receiving treatment for a serious liver ailment, Kramer learned that he himself was HIV-positive. Soon after, speaking before a packed house at New York’s Gay and Lesbian Center, Kramer challenged his audience with a question. “Do you want to start a new organization devoted to political action?” The answer was an emphatic yes.

Two days later, 300 people met to form the first chapter of the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP). The group’s media-savvy, in-your-face protests against the White House, pharmaceutical companies, Wall Street and the Catholic Church forced the media to pay attention to the epidemic,and took on entrenched bureaucracies.

On October 11, 1988, in a bid to hasten the approval of promising drugs to desperately ill patients, thousands of activists shut down the Food and Drug Administration for the day. It was the largest demonstration in Washington D.C. since the Vietnam War, and helped pushed the agency to fast track a string of effective experimental drugs.

By the early nineties Kramer had become a controversial, but nationally recognized figure—the gay movement’s eminence grise. In 1992 his play The Destiny of Me was nominated for the Pulitzer Prize and he is a two-time recipient of the Obie Award. In 1999, Time Magazine included him on its list of the 100 most influential people of the decade.

Since then, though he remains a committed activist, Kramer has focused on more creative pursuits. In 2001, after discovering extensive liver damage due to Hepatitis B, Kramer received a liver transplant.

The procedure did not reduce his bile. In 2004, days after the reelection George W. Bush, Kramer delivered a speech that he turned into a much-discussed book. He pointed out that despite an ongoing war and severe economic tribulations facing the country, the Bush campaign had effectively used homophobia as a primary tool to win the election. More controversially he decried the upsurge in unsafe sex among gay men as the apparent threat of AIDS had receded.

“Does it occur to you that we brought this plague of AIDS upon ourselves?” he wrote, in one of the book’s most provocative chapters. “I know I am getting into dangerous waters here but it is time. With the cabal breathing even more murderously down our backs it is time. And you are still doing it. You are still murdering each other.” Though his attack on the gay community resulted in an immediate furor, Kramer remains wary of Prep, fearful that that the unleashed promiscuity the drug promotes will result in another epidemic.

Now 82, Kramer is enjoying a renaissance of sorts.

A few years ago, The Normal Heart returned to Broadway for a smash run that netted the play an armful of Tonys. Soon afterwards it was remade as an HBO movie starring Julia Roberts.

In April 2015, Kramer released a mammoth new novel called The American People, Volume 1: Search for My Heart. An epic romp through American history from an unapologetically gay perspective, the book joyfully outs everyone from George Washington and Abraham Lincoln to Richard Nixon and Mark Twain. (Though Kramer insisted all his historical claims were true, many reviewers remained unconvinced.)

Earlier this year year HBO aired a much-praised documentary called Larry Kramer in Love and Anger, an intimate portrait of the icon by Jean Carlomusto that debuted at Sundance in 2015. Kramer is now at work on a sequel to The Normal Heart, which will reportedly also air on HBO.

But it hasn’t been smooth sailing for Kramer.

A few years ago, after suffering an unknown illness, Kramer lay near death at a New York Hospital in the company of his partner, architectural designer David Webster, who has lived with Kramer since 1991. (Kramer and Webster had also dated in the 1970s. In fact it was Webster’s ending of his relationship that inspired Kramer to write Faggots in 1978.) At some point, fearing the worst, Webster decided to make their partnership legal.

An old friend of the couple’s married them in Larry’s hospital room, where Kramer was lying incoherent and mute.

A few months later, Larry had made a miraculous recovery, and returned to his Fifth Avenue home.

“People have tried to write my obituary several times in my life,” he remarked later. “It always gives me great pleasure to prove them wrong.”