By Henry Giardina

In the first season of the original “L Word,” art plays a bizarrely large role. For a show so obsessed with the idea of looking, hiding, and being seen, it makes sense that the L.A. art scene, even in the early 2000s when the show opens, should be the backdrop for so many discussions, trysts, and trials. But the dominant feeling about “The L Word,” that groundbreaking, challengingly dated piece of work, is that for all its attempts to portray a true rainbow of queer life in L.A., it doesn’t do a great job of actually seeing its characters. From the horrid portrayal of Max, the show’s only trans guy with significant screen time, to the hatchet recon job done to Jenny, there’s a lot to find fault with.

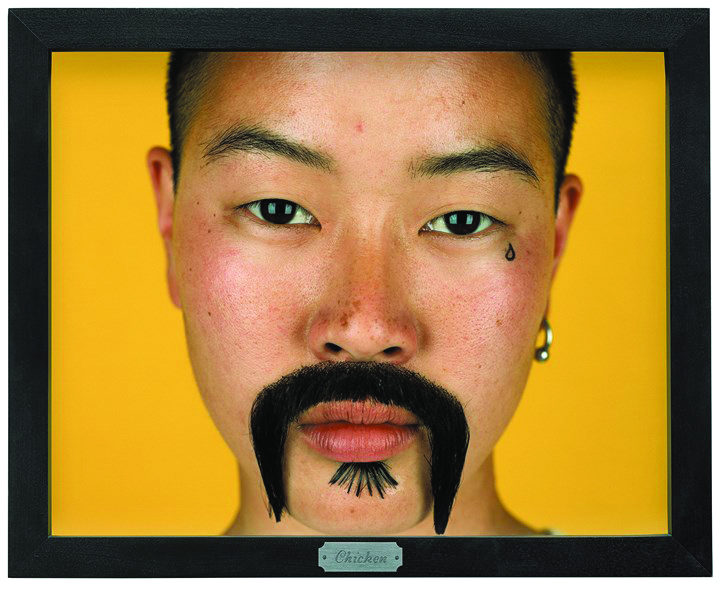

But let’s get one thing straight: the original “The L Word” knew queer art. Characters paid lip service to Lisa Yuskavage, Kiki Smith, and the legendary queer artist Catherine Opie in the first season. By the second, some of Opie’s decade-defining prints would start to be used in the show’s opening credits. Pictures of female-bodied folks with mustaches, breastfeeding butch mothers, and adolescent boys looking for a home within their gender became an unexpected focus of the show’s opening chorus with its self-conscious provocateur stance. Opie’s work was used as a kind of ideological stand-in for the show itself and what it thought it was doing. “See?” It seemed to say. “Look at us. We don’t care about the rules. We’re kissing in the glow of the men’s bathroom stall. We’re fucking up the patriarchy. We’re doing this.”

Sadly, for a generation of young queers, this was their first, and potentially only, exposure to Opie’s work. It was used for shock value during a time when the idea of a cis woman with a mustache was considered daringly outre. But shock value isn’t what Opie’s work boils down to. The L.A. legend has been photographing a complex array of gender expression for decades. Her solo show at MOCA in 1997, from which “The L Word” borrows its opening tableau, brought her photographic sense of exploration into sharper focus for the masses. Today, ideas about gender are changing rapidly as older norms become outdated. A new generation of art viewers (not to mention “The L-Word” consumers) are starting to expect more from representation that a barely-there nod to drag kings or a two-episode arc about HIV. Opie, from her corner of the art world, paved the way for that change. We owe her a lot more than a pop culture cameo. Without her vision of a truly genderless, or gender-complicated America, we might be just as much in the dark as we were back in 2002, when the radical idea of two girls kissing without a male audience had just started to take hold of the national imagination.