BY KAREN OCAMB | America left behind transgender individuals serving in the U.S. military when Congress repealed “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell in 2011— an issue addressed by former U.S. Navy SEAL Kristin Beck, a veteran of operations in Afghanistan, Bosnia and Iraq, and San Diego-based retired Navy FC1 Autumn Sandeen, who was arrested twice for protesting Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell with GetEqual in 2010.

Three years later, Sandeen made history as the first transgender person to have her gender identity officially changed by the Department of Defense. But it took another three years to end the discrimination. Last Friday, June 24, a Pentagon spokesperson announced that the DOD was finally lifting its ban on transgender servicemembers serving openly in the military by the end of July, if not sooner.

Aaron Belkin, the openly gay longtime expert on LGBT military issues as director of the Palm Center, found the Pentagon’s statement “heartening,” but expressed caution. “If that day arrives, successful implementation will depend on whether new policy follows medical consensus and applies the same rules to everyone.”

Ironically, on the same day the Pentagon announced its intentions to lift the ban, Lt. Shachar, Israel’s first openly transgender officer, spoke movingly about his own transition and the support he’s received from the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) at Congregation Kol Ami in West Hollywood. Kol Ami and out lesbian Rabbi Denise Eger have a special relationship with the Consul General of Israel for the South West, David Siegel, who attended the event with several staffers, along with representatives from other Jewish synagogues and organizations (such as the American Israel Public Affairs Committee or AIPAC) and West Hollywood’s Transgender Advisory Committee.

“There’s so much to do, so much to learn from each other,” Siegel said in an interview, noting that two years ago Israel signed an agreement with West Hollywood to share HIV research and experts. “America is really a pioneer that Israel can learn from. But on the other hand, our LGBT community goes back 40 years. It’s one of the first in the world. It’s very strong and Israel’s become a world center for the LGBT community.

“And in this case, we’re bringing such an amazing leader—the first transgender officer in the IDF,” he continued. “Israeli’s military is really part of the country. It’s where everyone goes, everyone has to serve. So if you happen to be different or in a minority, and you announce it— which he did—the military basically enabled him to become a leader of his own community within the military. Now he’s giving back. He’s helping the military with parameters and best practices for the next generation coming after him, so a real pioneer. So we’re very proud to be here.”

Eger, a longtime social justice advocate for the LGBT community who is also President of the Central Conference of American Rabbis, was central to the overwhelming voice vote passage last year of a transgender and gender nonconforming equality resolution by The Union of Reform Judaism.

“It was amazing,” Eger said at the time. “We believe in a Torah of inclusion and welcome for all and we made this dream come true yesterday.”

Eger made Kol Ami a welcoming place for Lt. Shachar, too. (IDF policy mandates that active duty personnel not reveal their last names.) He is on a U.S. tour that included a stop in Washington DC on June 21 where Shachar spoke at the Israeli Embassy’s first ever gay pride month event.

“This is the right of the whole world, to be free and to be whoever we want to be,” Shachar told the gathering, appearing to be referring to the shooting massacre at the gay Pulse nightclub in Orlando on June 12. Tel Aviv city hall lit up with a rainbow flag as an act of solidarity, The Times of Israel reported.

Israel’s ambassador to the U.S., Ron Dermer, noting that the Orlando shooter had professed allegiance to ISIS, wondered “whether he should add gays to his designation of Jews as the ‘canaries in the coal mine’ whose vulnerability signals threats to civilization,” The Times reported. “You are not alone,” Dermer said. “Israel stands with you.”

Shachar’s talk at Kol Ami seemed intensely personal, as the officer touched his chest as a sign of humility and perhaps an ongoing sense of his happy transition. He just had top surgery last month, paid for by the IDF. “I was wrong thinking it was impossible,” he said of being able to be his authentic self and have respect as an officer in the Israeli military.

Shachar’s story might differ from individual transition stories in other parts of the world—including the U.S. where trans service is still not allowed—but many outsiders will recognize the emotional and spiritual details in his journey to become whole.

Shachar, 24, was born in a small kibbutz to military parents—military service is mandatory for all Israeli citizens—and they soon discovered “I was not the girl that they thought I would be.” By age 2, Shachar wanted his head shaved; by 5, he demanded that his parents get rid of the dresses wasting space in his closet. And his parents “just agreed.” But as he walked around the kibbutz, he felt that “God put me in the wrong body. This must be a mistake. It’s not me.”

Shachar choked up. “Today I know how important it was to me” that his parents “let me be who I was” as a child. “Back then I didn’t know how to address the feeling in my stomach” about feeling different, not part of the girls but different from the boys.

By age 10, looking in the mirror with a shaved head, Shachar said to himself, “This is a young girl’s body. I am ruining her body.” But while his family and friends seemed to accept him as he was, he couldn’t shake his lack of confidence, his inability to share his true identity with others.

By 16, his only “solution” to be himself was to cut off his family, run away to another country where no one knew who he was and start a new life. But every time he had that thought, “it broke my heart.”

One day, a friend introduced him to someone who identified as transgender, born female, and Shachar had an epiphany. “My eyes just popped,” he said. “In this moment I thought, I’m not alone. There is a place for me in his world, maybe a place in my country, in my community, in my family. Maybe if he can be himself, I can, too.”

Three months later, Shachar came out, telling friends, “this is who I am, this is who I always was.” Everyone hugged him. “Finally, I was a boy, a man,” he said. “I was the man I always wanted to be.”

But then there was the IDF, to which everyone is drafted at 18. In addition to doing his part for national security, Shachar also felt the values instilled in him by his family to contribute and give back to society. “I wanted to be the best soldier I can be. It’s so simple,” he told himself, until he realized it wasn’t simple at all. He became terrified: how could he be a good, honest soldier while not being disruptive because of his gender identity?

It was a personal turning point. He could not let his gender identity stand in the way of his military service and the military demanded honesty. He decided to trust in doing the right thing and he told his commanding officers at his training base, though he rode the bus into the facility wearing a woman’s uniform with one pocket, not two. When policy determined he would not be allowed to wear a man’s uniform, one of his commanders got “creative” and came up with a compromise for Shachar to wear a looser-fitting unisex work uniform. Additionally, he was given a special time to shower on his own.

But he decided to hide his gender identity among his peers during basic training, bunking with female soldiers. “It was so important to succeed,” Shachar said.

Then he decided to become an officer and though he feared the sky would fall if he told his soldiers about his gender identity, Shachar had another epiphany. “It became clear: I don’t have a choice. I have a responsibility to these future soldiers to be honest,” he said. They had to be focused on the mission, which meant they had to trust him.

Shachar came “come out” to his team of 15 female soldiers, something he doesn’t really remember because of the stress. He remembers the silence, followed by lots of hugs. But during the last week of his officer’s training course—a week-long exercise when officers learn how to deal with the individual needs of each solider—a man asked out of curiosity: “Why do you wear a man’s uniform?”

Shachar sidestepped an answer until later when he said: “I wear a men’s uniform because that’s how I feel. My whole life I’ve known I’m a man, despite the fact that I was born a woman. I think, feel and identify as a man.”

After that, he came out to the whole unit. “I started as a female cadet and ended as a male officer,” he said.

After returning to his original unit of about 200 soldiers, Shachar found he was approached by several kids asking him how to join and have a successful service as an out trans person.

“I started to realize that there is something bigger” going on, he said, and he felt it was a responsibility to “make the best environment for them to succeed.”

Shachar decided to undergo the physical transformation with both hormone treatment and sex reassignment surgery, paid for by the IDF. Though he hopes on day to go to university and become an engineer, he is now counseling transgender cadets and servicemembers and is advising Brig. Gen. Rachel Tevet-Wiesel, IDF’s chief gender officer, on transgender issues and “how to do it,” covering everything they can think of. “We shouldn’t just trust common sense,” he said. “We are military. We should have regulations.”

Shachar has helped implement changes such as having soldiers identified by gender identity, not their gender at birth; trans soldiers can sleep on or off base; can wear a uniform that matches their gender; and have been given a special beard exemption, as is given to religious minorities.

Throughout his talk, Shachar emphasized that the IDF is far from perfect. But he also stressed that the IDF command endeavors to treat everyone equally through policy and practice, respecting the needs of each, especially since the military welcomes diversity and conscripts soldiers from all walks of life and religions in addition to religious and secular Israeli and Ethiopian Jews—including Druze and Circassian men, Bedouins, Christians and Muslim Arabs.

In another advance toward equality, last year on World AIDS Day, the IDF started to recruit soldiers with HIV —something that is anathema to a United States that still has a federal ban on blood donated by gay men, lest they be HIV-positive.

“This is an important move to accept these people in society, to lessen the social stigma and make them part of Israeli society,” said Col. Moshe Pinkert, head of the IDF’s Medical Services Department. “With this, we’re making them like all the people Israel.”

Shachar said that’s how he feels now, “normal” and confident. “The military treats me like everybody else. I am equal in the military,” he said. “Judge me only by my professionalism, my performance.” But while there is still “a lot of work” to be done, “to be part of the defense force and see integration as one of its goals is amazing.”

Interestingly, the same day Lt. Shachar spoke at Kol Ami in West Hollywood, the vote came in revealing that the “Leave” side of the Brexit referendum advocating got England to divorce itself from the European Union won, with chaos quickly ensuing and the British pound plummeting. Much of the “Leave” vote was born out of immigration and economic fears and a dark streak of nationalistic fervor. Such times have historically been conditions that have resulted in fascism, the mirror image of the diversity represented by Shachar in West Hollywood.

Rabbi Denise Eger didn’t react that explicitly to the Brexit vote—but she calmly cautioned America to take heed. “We live in a very fragile world in a fragile time. There are a lot of fears about the future in Europe,” Eger said. “In August, I’ll be traveling to Germany to work with Syrian refugees for a week in Germany. And it’s a scary time for the world. England took a snap shot of its own sense of the rules and where it wanted to be. They’ll have to work it out.

“But it’s clear to me that it’s a message to our own country to not give into the fear and hatred of the other,” Eger continued. “And having Lt. Shachar at Kol Ami—as the first openly trans officer in the Israeli Armed Forces—is an example of being always open to those who are different. My tradition teaches love your neighbor as yourself. It’s a simple guide. And would that England understood that they will not hold off a changing world by isolation. None of us can. We have to figure out how to live with our differences, learn with our differences and love our neighbors.”

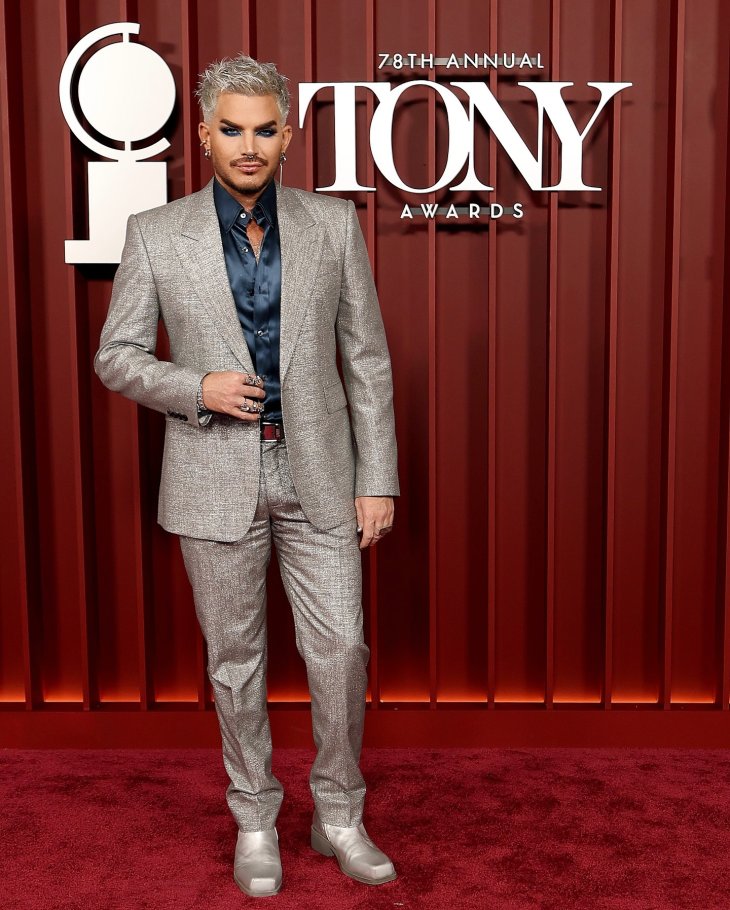

Shachar with James Wen and Karina Samala of the West Hollywood Transgender Advisory Board, Emat Laurence Block of Kol Ami, Lt. Shachar, and Rabbi Denise Eger