BY RIESE | Jeanne Córdova, the legendary lesbian activist, publisher, and writer, passed away early Sunday morning at the age of 67 after an extended battle with cancer. She was in her Los Angeles home with her partner of 25 years, radio talk show host Lynn Ballen, as well as her friends Jenny Pizer, Doreena Wong and Dina Evans.

Córdova’s contributions to the lesbian community cannot be overstated, and they will continue on, as she chose to bequeath $2 million to The Astaea Lesbian Foundation for Justice to create The Jeanne R. Córdova Fund. The Fund will be devoted to the support of organizations focusing on movement building, human rights and journalism with a specific focus on Latina lesbians from South/Latin America and South African women; lesbians, feminists, lesbian feminists, butch and masculine gender nonconforming communities.

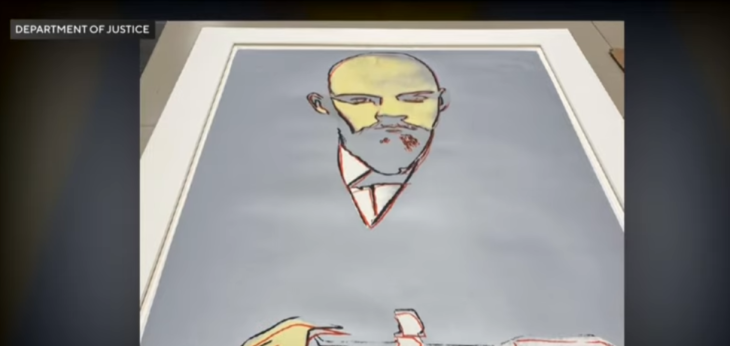

Cordova is pictured here at one of america’s earliest lesbian political gatherings, june of 1971.

“I feel strongly that we should not think heterosexually [about wealth], like ‘I’ll give it to some random relative that I’ve never met,” Córdova said of her decision to make this donation. “We need to think about giving to our gay or lesbian youth and institutions like Astraea or other lesbian organizations. They’re the ones who are nurturing our real daughters right now, around the world.”

In these infinitely more accepting times, it’s more important than ever to remember, pay tribute to, and celebrate the lives of foremothers like Córdova. Especially right here, in this space, right now, because we would not exist were it not for all the publications for lesbian, queer and bisexual women that came before us — the community they built, the stories they shared, the political issues they hashed out and the divisions they investigated. In an e-mail last year, Córdova told me she felt Autostraddle was “worthwhile in the same way” as her pioneering publication, The Lesbian Tide. It was an incredible compliment.

The Lesbian Tide began in 1971 as a newsletter for the Los Angeles chapter of the lesbian rights organization Daughters of Bilitis. In her 2015 “Letter About Dying, to My Lesbian Communities” quoted above, she recalled that “from the age of 18 to 21, I painfully looked everywhere for Lesbian Nation. On October 3, 1970, a day I celebrate as my political birthday, I found Her in a small DOB (Daughters of Bilitis) meeting. That’s when my life’s work became clear.”

However, The Tide‘s young radicals often clashed with elder DOB activists and in 1972, it split from the DOB with Jeanne Córdova as editor. “Bigger things were happening than DOB,” she told Rodger Streitmatter, as quoted in his book Unspeakable: The Rise of the Gay and Lesbian Press in America. “I was 23 years old and wanted to cover them my way.”

A survey in the late ’70s of Advocate readers found a whopping 97% of its audience to be men, and Córdova wanted The Lesbian Tide to provide for lesbians what The Advocate did for its community. The two most prominent lesbian publications of the ’70s — a veritable golden age for lesbian publications — were The Furies and The Lesbian Tide. Starting with about 100 readers, by 1977 the magazine had a circulation of 3,000 and was sold in eighty bookstores. It is estimated that in 1975, around 50 lesbian publications existed and collectively boasted around 50,000 readers, which unfortunately didn’t exceed that of The Advocate‘s circulation alone. It was much harder to reach out to and build community amongst lesbian women, who often lacked the economic mobility white gay men had greater access to because of The Patriarchy.

The Tide was specifically a lesbian feminist publication, defining lesbian feminists as “women who devoted themselves entirely to women for social, emotional, physical and economic support.” It abandoned fiction, a mainstay of other lesbian publications, in favor of news and reporting on cultural issues. “I didn’t want my lesbianism to be just a matter of sexuality,” Córdova said. “I felt it was more political than that really.”

The Tide solicited stories from readers around the country and prioritized lesbian voices, wholeheartedly refusing to use straight people or gay men as sources of information or funding. At a time when the position of women in American culture was even worse than it is today, this type of insular movement building was crucial and empowering. Despite the generally anti-trans sentiments of lesbian feminists of the era, The Tide had a lesbian transgender photographer, and Córdova recently told writer Anna Mollow “anyone who called herself a woman was welcome to serve on our staff.” More recently, Córdova also publicly supported the inclusion of trans women at the Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival.

Although what they were able to pay their writers wasn’t much — often only five dollars — it was important to Córdova that nobody was working for free. She was the only full-time employee of the magazine, making a salary of $7,500 a year (around $21k in today’s money) by the time the magazine folded in 1980. They struggled to survive off advertising solely from lesbian businesses and often directly asked their readers for money (in all caps, obvs).

The-Lesbian-Tide

The Lesbian Tide covered a myriad of issues and topics: politics, education, butch/femme roles, motorcycle racing, lesbian music, the Goddess movement, non-monogamy, dyke separatism and more. (You can read a sample issue of The Lesbian Tide here.) Córdova was also the first lesbian journalist to talk about lesbian BDSM, however, recalling in Unspeakable, “Feminists were obsessed with politically correct sex. We had more letters on our S & M coverage than any other subject in our nine years of publishing.”

The Tide‘s community carried over into real life, too: on a smaller, local level, they formed their own softball and football teams and did things like hosting fund-raising events for lesbian prisoners. In 1973, Córdova and the staff of The Lesbian Tide were key organizers of the National Lesbian Conference in Los Angeles, which was, at its time, the biggest gathering of lesbians ever. Previously, Córdova had organized the West Coast Lesbian Conference in 1971 and would go on to serve as a delegate to the first National Women’s Conference in 1977. In 2010, she chaired the Butch Voices Conference in Los Angeles.

The Lesbian Tide is only a one part of her prolific life’s work as an editor, writer and journalist.

As an investigative reporter and Human Rights editor for the Los Angeles Free Press, she interviewed activist Angela Davis and Emily Harris of the Symbionese Liberation Army. Throughout the ’80s and ’90s, she produced The Community Yellow Pages, an LGBT business directory. In 1987-1992 she published the The New Age Telephone Book and, from 1992-1994, produced Square Peg magazine, which (according to Unspeakable) focused on “the lesbian and gay good life.” It included club listings and an advice column with a lesbian and a gay psychotherapist, as well as featuring lesbian comics like Suzanne Westenhoefer and Lea DeLaria. Square Peg is also notable for its valiant effort to get Jodie Foster to come out after winning her Oscar for Silence of the Lambs (no luck). In 1997, she published The Spirit of Todos Santos, an arts & culture magazine serving the town of Todos Santos in Baja California Sur, Mexico.

She published three books, most notably When We Were Outlaws: A Memoir of Love & Revolution in 2011, which you should probably buy and read today. Her work has appeared in publications including The Guardian, The Nation, The Washington Blade, The Bay Area Reporter, The Advocate, The Lesbian News and The Los Angeles Village View. Essays have appeared in anthologies including The Right Side of History: 100 Years of LGBTQ Activism, Persistence: All Ways Butch and Femme, Untangling the Knot: Queer Voices on Marriage, Relationships and Identity, Persistent Desire: A Femme Butch Reader and Lesbian Nuns: Breaking the Silence.

Córdova was also very involved as an activist in the ’70s and ’80s, helping to found the Gay and Lesbian Caucus of the Democratic Party, serving as the media director to defeat the Briggs Initiative, and serving as president of the Stonewall Democratic Club.

After selling The Community Yellow Pages in 1999, she moved with her partner Lynn Ballen, the daughter of South African freedom fighter Frederick John Harris, to Mexico, where they co-founded The Palapa Society of Todos Santos, AC, a nonprofit focused on economic justice. They returned to California in 2007, where they co-founded LEX – The Lesbian Exploratorium and created the Lesbian Legacy Wall at ONE Archives (Córdova had been elected Board President of ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives in 1995). Ballen and Cordova continued hosting and planning history-themed lesbian feminist cultural events together in California throughout their lives together.

After selling The Community Yellow Pages in 1999, she moved with her partner Lynn Ballen, the daughter of South African freedom fighter Frederick John Harris, to Mexico, where they co-founded The Palapa Society of Todos Santos, AC, a nonprofit focused on economic justice. They returned to California in 2007, where they co-founded LEX – The Lesbian Exploratorium and created the Lesbian Legacy Wall at ONE Archives (Córdova had been elected Board President of ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives in 1995). Ballen and Cordova continued hosting and planning history-themed lesbian feminist cultural events together in California throughout their lives together.

She was diagnosed with colon cancer in 2008, and by 2013, it had metastasized to her lungs and to her brain. The chemo that fought the cancer also produced increasingly unbearable side effects. “The choice appears to be living with chemo forever off and on, or dying,” she wrote in her letter. “I will make that choice soon enough.”

Being an organizer and journalist in the lesbian, gay, feminist, and women of color communities—and loving it–has been the focal point, of my life. It has been a wild joyous ride. I feel more than adequately thanked by the many awards I have received from all the queer communities, and through all the descriptions and quotes in history books that have documented my role as an organizer, publisher, speaker, and author. Thanks to all of you who have given me a place in our history.”

This article was originally published online at http://www.autostraddle.com/