BY JOHN PAUL KING | When most younger Americans hear the phrase “Cold War,” it likely conjures vague impressions of backyard bomb shelters and spy vs. spy intrigue in far-flung corners of the world; but when confronted with the acronym “HUAC,” odds are good that many of them will be able to come up with nothing more than a blank stare. That’s a pity, because in today’s political climate, the history of the House Un-American Activity Committee should be an essential cornerstone of our cultural knowledge. For that reason alone, “Trumbo,” director Jay Roach’s new biopic about the most prominent member of the so-called “Hollywood Ten,” is a must-see.

I won’t go into detail about the anti-Communist hysteria in post-WWII America- after all, this is a film review, not a history lesson. Suffice to say that Dalton Trumbo was a prominent Hollywood screenwriter, called before congress to answer questions about his affiliations to the American Communist Party. Standing on his constitutional rights, he refused to cooperate; not only was he convicted of contempt, political pressure on the Hollywood establishment resulted in a blacklist which prevented the hiring of film artists who would not testify before the congressional committee, and he was left with no means to make a living despite being one of the most lauded scribes in the industry. “Trumbo,” recounts this history, and goes on from there to detail the story of the writer’s determined climb out of the ashes.

John McNamara’s screenplay focuses its attention on the man himself, giving us a whirlwind tour of his 13-year struggle, and intertwining the political with the personal through an emphasis on private scenes- as well as some healthy dashes of humor along the way. Through the periphery of Trumbo’s story, we are given glimpses of careers destroyed, lives ruined, and good people forced to betray their friends and their ideals. The result is a film that delivers a timely socio-political warning about governmental overreach, disguised as a safe, middle-of-the-road narrative.

Some might argue that the story of this dark chapter in Hollywood history might be better told by a less “Hollywood” movie. Even through its darkest moments, we know that the hero will triumph and the powers that oppress him will be vanquished. Most were not so lucky; their careers were permanently derailed, and the few survivors still had to wait years after the blacklist fell before getting work. In addition, though it strives to convey the complex ethics of the situation, it paints at least one character (notorious gossip columnist Hedda Hopper) as a clear target for the audience’s moral outrage without offering any satisfactory insight into the motivations which may have driven her. It should also be said that “Trumbo” “re-arranges” facts for smoother story-telling- standard movie-making procedure, perhaps, but regrettable, nonetheless.

Such quibbling aside, the film delivers a solid, honorable account of a determined man’s journey through darkness. Contributing to that is a meticulous recreation of the mid-century period, achieved through set and costume designs that convey the passage of time by reflecting subtle changes in the prevailing styles. More important, though, are the strong performances, provided by an ensemble ranging from familiar Oscar-winners to relative unknowns. A few standouts: Michael Stuhlberg, portraying actor Edward G. Robinson through suggestion rather than impersonation; John Goodman, hilarious as the no-nonsense producer who employed Trumbo during the blacklist; and Helen Mirren as Hopper, who reveals the tough-as-nails power-player masquerading as a blowsy busybody while still managing to give us glimmers of her humanity- despite the script’s failure to do so.

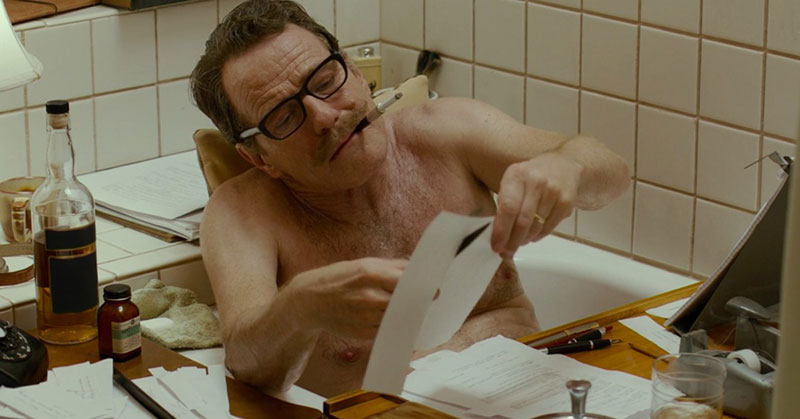

The impressive cast, however, rightly takes a back seat to Bryan Cranston, who displays his astonishing range with every subtle shift of expression. He completely inhabits the larger-than-life Trumbo with an authenticity that never makes him seem affected. He’s a delight to watch- the image of him doggedly typing away in the bathtub is bound to become iconic- but never afraid to show us Trumbo’s ugly side; and despite his exceptional work throughout, he saves the best for his final, moving recreation of a late-in-life speech that and leaves us with a powerful impression of Trumbo’s integrity.

That integrity, of course, is a given from the beginning of the film; but “Trumbo” is not meant to surprise. It is meant, rather, to retell of a story that should always be retold. As its postscript reminds us, the Communist witch hunt affected people in all segments of the population, not just members of the Hollywood elite. Though set in a time gone by, the film is chillingly contemporary; and if paranoia and political opportunism can combine to persecute a wealthy white man, then who is really safe? It’s easy to point out that none of us are Trumbo- but his story serves as a reminder that he could be any one of us.

Director: Jay Roach

Writers: John McNamara, Bruce Cook (book)

Stars: Bryan Cranston, Diane Lane, Helen Mirren

PLAYING: ArcLight Hollywood and Sherman Oaks, Landmark Theatres