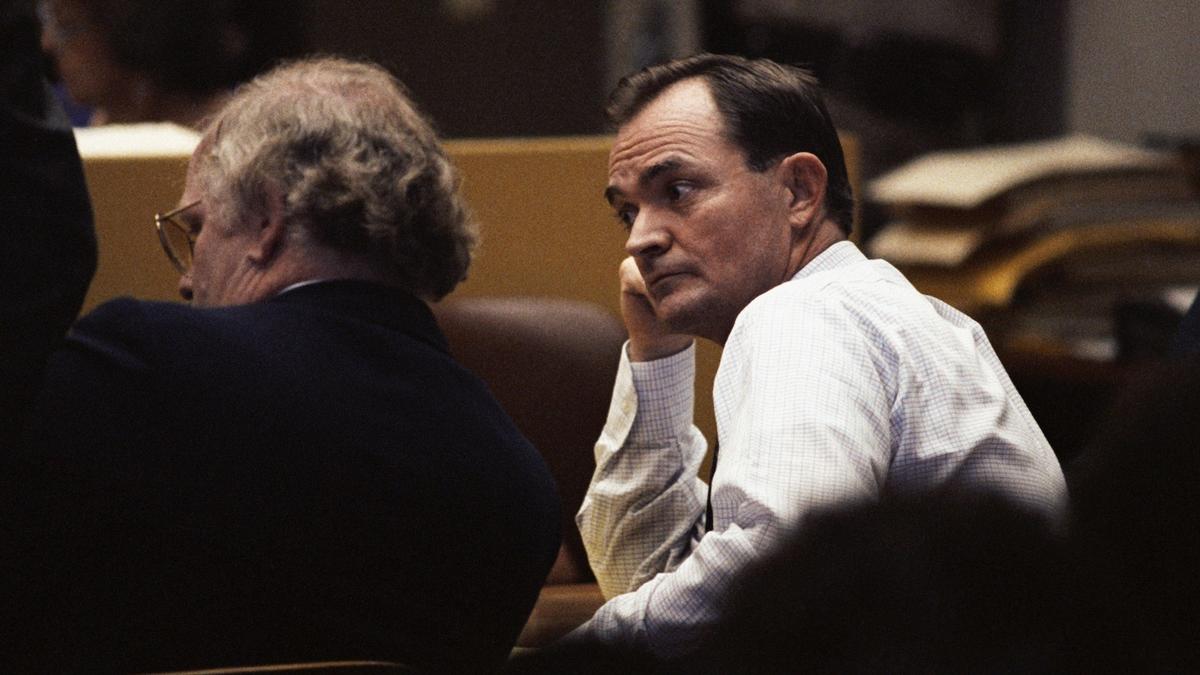

BY MATTHEW BAJKO | For nearly 30 years Randy Kraft has sat on California’s death row attempting to clear his name. A gay man given the nicknames “the Scorecard Killer” and “the Freeway Killer,” Kraft has been described as one of the “deadliest and most depraved serial killers” in the state’s history.

In May 1989 a jury convicted him of killing 16 men over the course of 11 years in southern California and, that November, recommended the death penalty. Prosecutors had also tied him to the deaths of eight additional men in Oregon and Michigan.

In the summer of 2000, with Kraft’s appeals of his verdict in state court exhausted, the California Supreme Court upheld his conviction and death sentence. Kraft then turned to the federal courts to seek a new trial of his case. He has been mired in the federal appeals system ever since, and on numerous occasions, he has petitioned to have a new federal public defender assigned to represent him.

Randy Kraft – The Scorecard Killer by billyjones2k14

To this day Kraft has never confessed to the murders he was found guilty of committing. And other than an interview with a Los Angeles Times reporter six months after his arrest in 1983, Kraft has not spoken publicly about his case other than through copious court filings over the years.

During his jury trial, Kraft did not testify on his behalf. After the trial court judge refused to grant his request to testify about only one of the murder charges he was facing, he opted, based on the advice of his attorneys, not to take the stand to defend himself.

Kraft, 71, contacted the The Pride Los Angeles last fall about his desire to publicly discuss his case before he dies.

“This has been bottled up so long,” a graying Kraft, dressed in dark blue pants and a light blue shirt, said during an interview in March over a lunch of a microwaved southern fried chicken sandwich and a cheese and bean burrito. “I am getting older. I am going to die here. And I am frustrated my attorneys aren’t saying these things. If I don’t say something it will never be said.”

“This has been bottled up so long,” a graying Kraft, dressed in dark blue pants and a light blue shirt, said during an interview in March over a lunch of a microwaved southern fried chicken sandwich and a cheese and bean burrito. “I am getting older. I am going to die here. And I am frustrated my attorneys aren’t saying these things. If I don’t say something it will never be said.”

Over the course of 10 months, through written correspondence and three in-person meetings at San Quentin State Prison, Kraft repeatedly maintained his innocence and alleged he had been the victim of a criminal and judicial system biased against him because of his sexual orientation.

“To begin, I did not kill Terry Gambrel,” Kraft wrote last November in one of his first letters, referring to the Marine found slumped over in the passenger seat of his car when two CHP officers pulled him over on Interstate 5 in Orange County for suspected drunk driving late one night 33 years ago. “And neither did I kill or assault any of the other persons as the authorities claim. Notwithstanding that, I have been imprisoned since May 14, 1983, some 32 years, nearly half of my life.”

Nonetheless, several times Kraft stressed that he has no expectation of ever stepping foot aside of jail. At his age, he expects he will die an inmate.

“Even if the federal courts agree with everything I am saying and sends it back to the state courts, I will still die in here because it takes so long. That is just the way it is,” said Kraft during a May interview. “I think the court is waiting for me to die. It is death penalty by attrition.”

Odds are Kraft, one of 741 death row inmates in the Golden State, will die of natural causes rather than be put to death. As the The Pride noted in September, California has not executed anyone since 2006. Two years ago, a federal judge ruled that the state’s death penalty system was unconstitutional because it is arbitrary and plagued with delays.

And, for the second time in four years, the state’s voters this fall are being asked to abolish the death penalty. Polling indicates the fight to pass Proposition 62 next Tuesday on the November 8 ballot is tight, with the latest poll released this week by Stanford’s Hoover Institution showing voters evenly split on the measure.

A competing ballot measure, Proposition 66, which would keep the death penalty in place and accelerate the state appeals process, had been trailing with voters. But the Hoover Institution poll found it leading 38 to 24 percent, with as many Californians undecided as they are in favor of the measure.

“It looks like it will pass, and then at the last minute, everyone changes their mind,” said Kraft about the death penalty repeal efforts. “Maybe it will pass this time.”

In 2012 many of his fellow death row inmates were rooting for defeat of the measure, said Kraft, since it would not only have dismantled death row but have sent the prisoners to various prisons around the state.

“Last time it was on the ballot, some people here didn’t want it to pass because they didn’t want to be transferred elsewhere,” recalled Kraft.

Should this year’s Prop 66 pass, Kraft said he wouldn’t mind being transferred to a prison closer to Orange County, where his sister, who is in her 80s and frequently speaks with him by phone, lives and could potentially visit him. Yet he expressed some misgivings about leaving San Quentin, it having been his de facto home now for close to three decades.

As for being released from prison, Kraft admitted he doesn’t see himself resuming his old life. As he recalled telling one of his former attorneys, who asked what he would do if his conviction was overturned, Kraft replied, “My life is here now. Almost all of the people I care for are here. I don’t have any former life to return to; it is obliterated. I don’t pine for release; my life is here. I’ll die here, and that’s OK with me.”

The fact that Kraft is still alive continues to cause outrage in Orange County. In 2013 the local magazine Orange Coast ran a story titled “Why Isn’t Randy Kraft Dead?” and quoted several of the jurors who convicted Kraft expressing disbelief that he has yet to be executed.

The author also spoke with Max Gambrel, a cousin of Terry Gambrel who grew up next door to him in Indiana. He expressed mixed emotions about Kraft, saying that while he has thought about killing him himself, he is also “glad” he remains behind bars.

“He loved his freedom, and the longer he’s in jail … it’s the only justice my family has,” Max Gambrel told the publication.

The night of his arrest

Born in Long Beach, the youngest child of four and the only son of parents Opal and Harold Kraft, Randy Kraft grew up largely in the Orange County town of Midway City. He attended Claremont Men’s College, from which he graduated in 1968 with a B.A. in economics.

He then joined the U.S. Air Force and was stationed at Edwards Air Force Base in southern California. He was discharged in 1969 after disclosing his homosexuality to a superior and moved back home with his parents.

Seven years later he had met Jeff Seelig, who worked as a baker, and the two were living together in a home in Laguna Hills. Kraft was working as a computer consultant, a job that often had him traveling to other states.

The night of May 12 Kraft said that he and Seelig had gotten into a fight about money and the next morning Seelig left to attend a chocolate show in Los Angeles. That night he thought about driving up to join him, but because of their argument the day prior, he instead headed south to San Diego. He had a few drinks at a gay bar called The Brig and set out to return home sometime after midnight.

He stopped at a rest area off Interstate 5 not far from Camp Pendleton to clear some bottles and trash out of his car. There is where he encountered Gambrel, 25, a Marine stationed at El Toro, California.

“He was sitting down, holding stuff in his lap near the trash can in the parking lot. He looked out of sorts and I asked him if he was OK,” said Kraft. “He didn’t say anything to me other than he said ‘El Toro.’ I thought he was drunk or whatever and would take him to the base.”

A frequent cruiser of rest areas for gay sex hookups, Kraft said Gambrel “didn’t look the type” and Kraft helped him to his car. Eventually, they drove off toward the (now decommissioned) Marine Corps Air Station near Irvine. Kraft estimated they had been in the car for roughly 20 minutes, with Gambrel not saying anything and “drooling out of the side of his mouth.”

He told the The Pride that his car was weaving not because he was drunk but because he was trying to help Gambrel and simultaneously drive.

“I was shaking him, trying to wake him, shouting at him, trying to see if anything was in his mouth blocking his airway, looking to see if he was wounded or bleeding,” wrote Kraft. “Then I noticed the lights of the CHP patrol car that was pulling me over.”

It was near San Juan Capistrano where the two CHP officers pulled him over and conducted two sobriety tests on him. Kraft insists he was told he had passed the tests but the officer wanted to run his license. At that point the other officer, who had been trying to rouse Gambrel, called over to his partner who then “roughly handcuffed and shoved” him, Kraft said, into the back seat of the patrol car.

“I didn’t think the cops would take Gambrel to a hospital. I thought they would initiate CPR or do whatever was necessary,” wrote Kraft in one letter. “Instead they did nothing and at first tried to prevent the paramedics from starting CPR. Those first 4-5 minutes are critical, and the CHP did nothing.”

According to court documents, the one officer found Gambrel with “no pulse and was not breathing. Upon lifting a jacket from Gambrel’s lap, (he) observed that Gambrel’s pants were unbuttoned and pulled down between his waist and his knees so that his penis and testicles were supported by the crotch of the pants. The crotch area was wet.”

A paramedic, according to court documents, said that Kraft told him that he had given Gambrel some of his Ativan, which he had been prescribed to treat panic attacks. Kraft, however, claims Gambrel stole the Ativan and that he did not know he had taken any that night until after seeing the police reports.

At trial a doctor testified that Gambrel had died from asphyxia due to ligature strangulation and that the ligature “consisted of a strap that had been tightened” around his neck, according to court documents.

Kraft repeatedly insisted to the The Pride that Gambrel was never dead in his car.

“Had the CHP realized that, things would have unfolded much differently,” he wrote. “But they assumed he was dead and that I had killed him and was driving around for hours with his body in the passenger seat.”

In the course of their investigation, the police found in Kraft’s car a list of names split into two columns on a piece of legal pad paper. The prosecution argued it was coded references to Kraft’s numerous murder victims over the years and used it in court to tie him to their deaths.

On several occasions in his letters, and in speaking to the The Pride, Kraft disputed that characteristic of the document. He said it was a list of people he was going to invite to a surprise housewarming party he planned to throw for Seelig, as they were redoing their bathroom and installing a spa to an outdoor deck.

Written out in mnemonics, Kraft explained, “One column was the names of people I wanted to invite and the other column were maybes. It was in code so he wouldn’t recognize it.”

The purported “murder list” would later factor into why Kraft’s attorneys advised him not to take the stand at trial. In explaining their thinking, Kraft wrote, “If one believed what the prosecutor claimed about the list – that it is a list of murder victims – that it amounts to a confession. The prosecutor claims the list is a confession, but he reaches that conclusion by psychic powers, imagining what was in my mind when I wrote it.”

Over the years Kraft learned that three of the judges who handled his case, including the presiding trial judge, the late Donald A. McCartin, had served in the US Marine Corps, and therefore, he contends should have recused themselves. And he maintains a key piece of evidence in the case – his fingerprint on a glass – “was manufactured.”

The appellate courts, however, have rejected Kraft’s contention that he should have been tried solely for the death of Gambrel and not had that charge be combined with the murders of the 15 other men.

“I didn’t get a fair trial,” said Kraft. “The government turned it into a serial killer trial.”

— Matthew Bajko reports for San Francisco’s Bay Area Reporter