BY TROY MASTERS | The United States federal government has recognized as legally valid the April 1975 same-sex marriage of Richard Adams and Anthony Sullivan, approving the “green card” petition that Adams filed in 1975 for his husband, an Australian citizen. After Adams died in December 2012, Sullivan sought to have the Immigration Service recognize their marriage and grant a green card to him as the widower of a U.S. citizen.

The green card, granting Anthony permanent resident status in the United States, was issued on the 41st anniversary of his Boulder, Colorado marriage to Richard — a same-sex marriage that remained in the record and which was never invalidated by Colorado officials.

The green card was recently delivered to the Hollywood apartment Richard and Anthony shared for nearly four decades.

Immigration authorities, in 1975, famously refused the couple’s “green card” petition, saying they had “failed to establish that a bona fide marital relationship can exist between two faggots.”

A ten year legal battle followed, as Richard and Anthony brought a lawsuit against the Immigration and Naturalization Service (now called United States Citizenship and Immigration Services) in federal court, becoming the first gay couple to sue the U.S. government for recognition of a same-sex marriage.

When the final ruling came from the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals in 1985 they were forced to leave the country.

Together, they endured expulsion from the United States, bounced from country to country and would go on to suffer decades of indignities; upon return to the U.S. in 1986 they were forced to keep a very low profile, living in fear that Anthony would be deported. It was a fear finally eased a year before Richard’s death in 2012 when the Obama administration issued a memo to protect low-risk family members of U.S. citizens from deportation, including same-sex partners of American citizens.

As newlyweds, Richard and Anthony could never have imagined that 41 years later the White House would ask the Director of USCIS to issue a direct, written apology to them. Nor could they have imagined that, in 2016, the very same downtown Los Angeles Immigration office that denied Richard’s green card petition for Anthony with such offensive language would, at long last, recognize their marriage and take the position that Anthony should be treated the same as all other surviving spouses under U.S. immigration law, with the dignity and respect he deserves in accordance with recent Supreme Court rulings.

Lavi Soloway, their Los Angeles-based attorney, says the federal government’s recognition of their 1975 marriage is groundbreaking because it affirms that the constitutional protection of fundamental personal liberties, including the right to marry, extends to a marriage entered into by a same sex couple that took place decades ago.

“The unique and historic nature of this case cannot be understated. The U.S. government not only apologized directly to Anthony Sullivan, but, for the first time since the Supreme Court established the right of same-sex couples to marry as a protected, fundamental liberty—the Immigration Service has shown its willingness to correctly apply recent Court rulings and to recognize as valid this same-sex marriage that took place in 1975. Undaunted by setbacks in the 1970s and 1980s Richard and Anthony never wavered in their belief that their marriage was valid and should be treated with dignity and respect. Eventually the Supreme Court and the Immigration Service caught up with them,” said Soloway.

“This outcome is an example of the potentially far reaching ripple effects of the Court’s ruling in Obergefell,” Soloway added.

“In 2014 we asked USCIS to take the steps necessary to reopen Adams’ 1975 petition in light of the Supreme Court ruling striking down the so-called “Defense of Marriage Act” and subsequent victories by gay couples in marriage equality cases.” The last ruling on their petition had been issued by the Board of Immigration Appeals in 1978,” explained Soloway.

“After the Supreme Court ruling on Marriage Equality, USCIS acted on our request to apply, constitutionally valid principles to the 1975 green card petition. As a result, on December 1, 2015 the Board of Immigration Appeals ordered the petition be reopened and the original denial reconsidered,” he said.

In January 2016, Adams’ original petition was approved and, because he was deceased, it was converted by USCIS into a widower’s petition, allowing Anthony to move forward with his green card application.

A LOVE STORY

Theirs is a monumental love story that began in “The Closet” only to make history and has come to embody the entire narrative arc of the modern gay rights struggle and the fight for marriage equality.

They met in 1971 at “The Closet,” a Los Angeles gay bar, at a time when LGBT people were referred to as ‘homosexuals,’ or ‘faggots,’ were denied travel visas, classified as mentally ill, barred from many professions — a time when most of us were rejected by our families, could be imprisoned for having sex, were routinely evicted from our homes, easily fired from our jobs, and few authorities cared if we were beaten in the streets or even killed.

It was a time when our very right to existence was challenged at a near cellular level, even before AIDS.

Falling in love was one thing but finding a way to stay together was an entirely separate matter: Anthony was in the United States on a 90 day tourist visa. But they decided they would pursue all legal avenues to stay together, a story masterfully told in the 2014 documentary Limited Partnership, produced by Thomas Miller and Kirk Marcolina.

That documentary played a powerful role in the resolution of their story.

In the early 1970s, since Anthony was unable to obtain a long-term visa, they made risky border crossings to Mexico every 90 days to renew his tourist visa.

The United States Immigration and Naturalization Act of 1952 was the law of the land, declaring homosexuals ‘excludable at entry,’ along with ‘perverts’ and ‘psychopathic personalities.’

“We had a cloud over us,” Richard said in a documentary about their lives called “Limited Partnership,” which was broadcast on PBS in 2015. “Anthony didn’t want to get closer (in case a separation would occur). So, we had to start thinking of a way to stay together. There’s no way two men could stay together,” he told filmmakers.

If Richard and Anthony had been a heterosexual couple they would have been able to fill out some forms, attach a marriage certificate and eventually go through an interview process that would result in the foreign spouse receiving a Green Card.

Soloway, says “When Anthony and Richard met in the early 1970s, as citizens of two different countries, there was no country in the world that provided for immigration for same-sex couples. There was no country in the world that was even discussing it. They had no country to go to.”

“We eventually realized,” Anthony said in Limited Partnership, “that the only thing that was stopping us from being able to remain together was the fact that we were two men and couldn’t get married.”

“And then…out of the blue, out of nowhere, we saw the most incredible news,” he said, referring to a Boulder, Colorado County Clerk, who created a huge controversy four decades ago when she issued the nation’s first marriage licenses to gay couples.

That was 1975. It is a seminal event in LGBT history that has been largely forgotten, only six years after the Stonewall riots in New York’s Greenwich Village.

“At the time I didn’t even know any gay couples,” Clela Rorex told Limited Partnership. “I was being faced with a very profound moral issue: ‘would I discriminate against two people of the same sex when I had been so involved in fighting discrimination against women,” she said.

She sought legal counsel from Boulder’s district attorney who determined there was “nothing in the Colorado marriage code that would prohibit” her from issuing marriage licenses to two people of the same sex.

Rorex began issuing licenses to same-sex couples. In a 1975 article in The New York Times, Rorex suggested that marriage inequality could be “resolved by eliminating the gender words. Her reasoning, she said, was “Who’s it going to hurt?”

By week’s end, her defiance was top of the fold news.

Richard and Anthony were elated: “They’ve allowed these marriage to go on for a month. Johnny Carson has talked about them, so the government can’t claim ignorance. Therefore, these must be valid!”

They flew with friends and their Metropolitan Community Church minister to Boulder to get married. “We got the license in the morning and immediately got married.” Anthony proudly said in Limited Partnership.

“The press picked up on it and it was really quite chaotic,” Richard said. “We were conscious that if we weren’t careful it would become a three ring circus, which we didn’t want.” But it did and the impact of that publicity was was devastating.

“All of a sudden everyone looked at me differently,” Richard said. He was harassed and ultimately terminated from his job of ten years and his relationship with some members his large Filipino family soured.

Anthony’s mother wrote “a missive” from Australia, telling him she “could endure no more. Perversion is bad enough…but public display never,” she wrote, signing the letter “It is finished.” She never contacted him again and disinherited him.

One of the first things the couple did after they married was to return home to Los Angeles was to apply for spousal green card.

Weeks later an official response came from the United States Depart of Justice Immigration and Naturalization Services office in downtown Los Angeles: “You have failed to establish that a bona fide marital relationship can exist between two faggots.”

But in case that wasn’t clear enough the Justice Department sent a second letter: “neither party can perform the female functions in the marriage.”

Anthony was certain he would be forced to leave the country.

Word of the “faggot” letter quickly spread throughout what was already a well-organized gay community in Los Angeles. MCC’s Reverend Troy Perry and 500 people protested at the Federal Building in downtown Los Angeles. “Justice! Justice! Justice!,” chanted the placard wielding protesters.

Anthony told The New York Times that his marriage to Richard was a test of the immigration laws that permit a foreign spouse to remain in this country: “we wanted to have the full benefits of other married couples — income tax returns, inheritance, wills and so on.”

But “rogue” activism was frowned upon by many of the emerging legal and advocacy organizations who felt the case was of little strategic value. “Some of our so called movers and shakers told us they weren’t interested in the case because we were a losing battle; the “faggot letter” had gotten too much attention,” Anthony says.

“Talk about a bunch of hens in a snit!” Anthony says of being confronted by one “leader” at a fundraising dinner. “He grabbed a white linen napkin off the table and, crunching it in his hands, and said ‘We will make you understand who is in control of this movement!’”

The couple was determined to pursue a legal course of action and hired a private attorney, David Brown, a Los Angeles constitutional lawyer. Brown told the media that gay couples had existed since the dawn of time and that equal rights should be afforded them.

LGBT equality was barely on the radar in the mid and late 1970s: The Supreme Court ruled that homosexual acts were illegal, Anita Bryant was leading a national crusade against gay rights laws in Florida and elsewhere, California was embroiled in a contentious debate about whether gays and lesbians should be allowed to teach in public schools and Harvey Milk was assassinated in San Francisco. Demanding the right to marry seemed, well, ridiculous.

The couple persevered, filing suit in the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals.

“The case, Adams v. Howerton, sought to force the immigration service to recognize their Colorado marriage so that Anthony would be allowed to remain in the United States permanently as the spouse of a U.S. citizen. Their argument — that to discriminate against them because they were two men was a violation of their constitutional rights — is familiar and obvious today, but at the time it was unheard of,” said their attorney, Lavi Soloway.

Their argument was quickly shot down by the U.S. District Court Judge who ruled in the case relying on a now debunked justification for anti-gay discrimination: “marriage was intended to unite a man and a woman for the purpose of propagating the species.”

The case was appealed and in 1982 the Supreme Court had the last word on the case, refusing to hear it.

The only option left to the couple was to pursue another immigration hearing to make an appeal. In 1984 they requested that Anthony be permitted to stay in the United States because deportation would cause Richard “hardship” as his spouse. The request was denied when the Judge in the case disagreed that Anthony’s deportation would cause “hardship greater than that which would be faced by anyone being deported.”

They appealed that decision to the Federal Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit.

Anthony, recalling that hearing, says the “The quality of argument by our opposition was not good. The INS lawyer got the countries mixed up, our names mixed up and finally, in desperation, she said ‘well, he can go back to Australia and have another one of those… relationships.”

In what is surely the most striking alignment of the stars in their story, it was future United States Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy, then an Associate Judge on the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, who ruled against Richard and Anthony, setting Anthony’s deportation in motion. Kennedy wrote that he found “no extreme hardship to Sullivan because he is not ‘a qualifying relative’ to Adams.

It is poetic that the man who ordered such a callous action against a same-sex couple would, thirty years later, write perhaps one of the most beautiful — and certainly most consequential — gay rights decisions ever handed down by the Supreme Court of the United States.

In 2015, writing for the majority in [the case known as] Obergefell vs. Hodges, Anthony Kennedy said same-sex marriages were protected by the United State Constitution. “Their hope is not to be condemned to live in loneliness, excluded from one of civilization’s oldest institutions. They ask for equal dignity in the eyes of the law. The Constitution grants them that right,” he wrote.

In 1985, facing deportation, Richard and Anthony had exhausted their appeals. There was no court left except the court of public opinion. So they turned to popular talk shows of the time. In a scene from Limited Partnership that featured a clip from The Today Show, an Immigration and Naturalization Service spokesman calls Anthony out: “Do you intend to leave our country on the 23rd of November?”

Richard replied for Anthony, “We are both leaving; we are not going to be separated.”

They became men without a country, forced to leave their friends and all their worldly possessions behind and headed to the airport.

As they arrived at LAX, they faced what Anthony called “a media circus” as they boarded a flight to London. Dozens of friends and family gathered to say goodbye. “It felt like death,” said Richard.

“We floated around the continent for many months,” said Anthony, until one day they both realized, “We need to be back home in Los Angeles.”

They decided to risk everything. Already experienced with crossing the Mexican border, they decided to fly to Mexico and re-enter the United States by car. “I was shit scared,” said Anthony in Limited Partnership. The American border guard simply waived them through.

Once home, Richard and Anthony had no options except to hide out and attempt to make a life on the margins of society.

The AIDS crisis began to hit close, devastating their family of friends and intensifying their sense of isolation. “The late 80s and early 90s was a horrible period for all of us,” said Anthony.

But then a small window of hope began to open, and, in forward and backward steps, gay rights began to advance. ACT UP broke the scientific and government wall of silence around AIDS. The Bush administration presided over reform passed by Congress in 1990 that removed the restriction on LGBT people entering the U.S., though HIV+ people were barred from entry. Then in 1992, the Democratic candidate for President made a major play for the gay vote and defeated the incumbent A protracted national debate ensued about gays in the military resulting in the uneasy compromise known as “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” which arguably, for the first time, officially allowed lesbian and gay servicemembers to remain in the armed forces. Protease Inhibitors slowly began to transform AIDS from a death sentence into a chronic, manageable illness. A case brought in Hawaii began a national conversation about gay marriage rights, catapulting the obscure subject into the spotlight as a political wedge issue and the passage of the Defense of Marriage Act by Congress.

The isolation and hiding required to stay together took a toll on both of them. Richard, in the documentary Limited Partnership said, “It’s 2002 and we are more in the closet on one level now than when we first met.”

By the mid-2000s the debate over gay marriage engulfed the nation and the marriage equality movement emerged. Vermont offered legalized civil unions, following the example of cities like San Francisco and New York which created domestic partnership registration in 1989 and 1993, respectively. But losses followed in court — New York, Maryland, Washington, Arizona, Indiana.

By 2004, a coordinated campaign to boost evangelical turnout for George W. Bush’s reelection saw 11 states pass constitutional amendments to ban gay marriage. More states followed in 2006 and by 2012, gay-marriage bans had been put before voters in 30 states and won every everywhere. For every step forward for gay marriage, there seemed to be many more steps back.

Those halting steps emboldened Richard and Anthony as they became more righteous about their story, even though Anthony still faced immigration action. “Richard and I have never budged on the concept that the Boulder marriage was legitimate — it’s still on the books,” Anthony told the Washington Post.

In early December 2012, as Richard was dying of cancer, Soloway met with his clients and urged them to consider remarrying in nearby Washington state. They reluctantly agreed, thinking of it as a renewal of their vows rather than a new wedding. But Richard passed away the next day.

Sullivan’s despair was absolute but he was resolute that his relationship with Richard be honored with the dignity and grace civilized societies offer widowers. “I wrote to President Obama,” he said.

“I requested, basically for Richard, an apology for the faggot letter, because I felt that as an American citizen, he didn’t deserve to have that on his record,” Sullivan said. “Because he loved his country.”

León Rodriguez, director of U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services wrote on behalf of the President: “This agency should never treat any individual with the disrespect shown toward you and Mr. Adams,” Rodriguez wrote. “You have my sincerest apology for the years of hurt caused by the deeply offensive and hateful language used in the November 24, 1975, decision and my deepest condolences on your loss.”

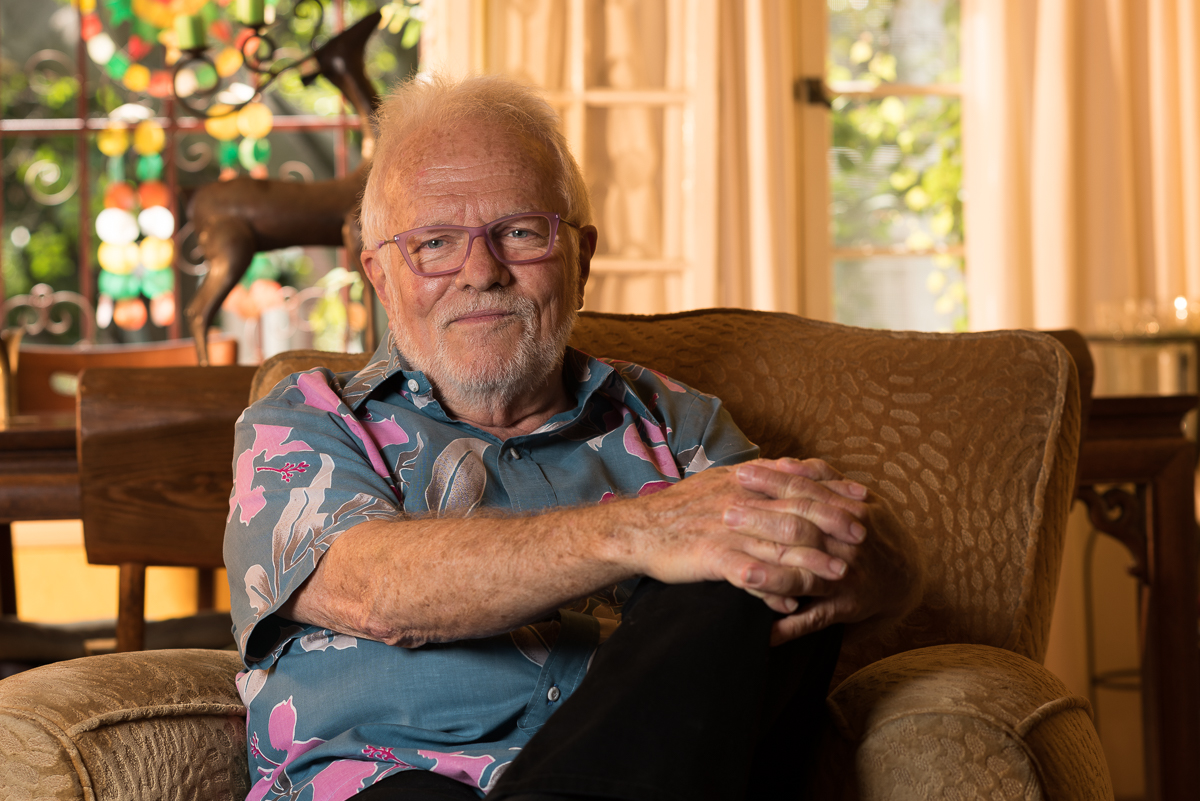

With federal recognition of their marriage and green card in hand, Sullivan is filled with wonder about the full circle of his life. “The same office that said we had failed to establish that a relationship can exist between two faggots now says yes. And on the day of our anniversary!”

Thumbing through a now historic folder of documents, Anthony looked at his hands and then gazed directly ahead, with a tear rolling down his cheek, and said “I desperately wish Richard was here with me for this.”

Of all same-sex married couples, Richard Adams and Anthony Sullivan now take their place in history as having the earliest legally recognized marriage in the world.

Sources: Limited Partnership, Washington Post, The New York Times, DOMA PROJECT, USCIS, The White House, Anthony Sullivan, The Los Angeles Times, One Archives